1992. Only a few weeks after his twenty-first birthday, our sonDavid died in a fall from the top floor of a high-rise block of flats behind the Merrion Centre in Leeds. I see it every time I drive to Leeds .

World Suicide Prevention Day was last month, Sept 10. As ever, I’m out of synch with the rest of the world, but it can’t ever be too late to write this post. Just over five years ago, two people I love found their son dead in their living room. He was about the same age as mine was when he killed himself. I remember I wrote to them and said something like: people will tell you they can imagine what you’re going through. They are wrong. More thoughtful people will tell you they can’t imagine what you’re going through. They are nearly right. The fact is, you can’t imagine what you’re going through.

Three good friends of mine, all the same age as me or thereabouts, have died in the last 18 months. Two, apparently fighting fit and well, died of sudden catastrophic heart attacks. One died after a long and painful illness. We grieve for them, but we understand our grief. Their deaths are sad, they diminish us, but we understand this natural process. It doesn’t accuse us. But when someone you love takes his own life, when it comes without warning, it’s inexplicable, bewildering, devastating. It makes no sense. The world makes no sense. You are made helpless with guilt; you believe you are to blame, that you could have prevented it if only…..

This happens to tens of thousands of people every year. The statistics are terrifying. The websites you can visit will tell you:

Suicide is the single biggest killer of men aged under 45 in the UK. In 2015, 75% of all UK suicides were male.

Men and boys are often more vulnerable to taking their own lives because:

- They feel a pressure to be a winner and can more easily feel like the opposite.

- They feel a pressure to look strong and feel ashamed of showing any signs of weakness.

- They feel a pressure to appear in control of themselves and their lives at all times.

Most suicidal people don’t actually want to die, they just want to remove themselves from an unbearable situation, and for the pain to stop.

There’s a lot of support and advice available for people who are worried that someone they know may be a suicide risk. Advice like this:

So how will you know?

You ask. It sounds scary, but the best thing to do is talk about it.

Saying something is safer than saying nothing. Trust your gut and start the conversation

What to say

Not too much. Above all, LISTEN

For me, and for my family, it was all too late. Because we had no idea, because there was no warning sign we could pick up on. There was just the immutable fact that our David had killed himself. We are tight as a family, we comforted each other, but we go on living with the bewilderment and loss and overwhelming guilt. It never quite goes away. So I’ll dedicate this post to all the families who have lost a child, a sibling, a parent, a partner to suicide, and I’ll talk about the long long process of finding the serenity to accept what cannot be changed. I’ll tell you our David’s story.

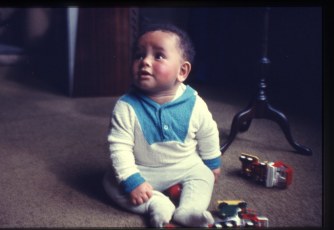

Two of my five children were adopted, and our David was one of them. Against all the rules, we met his birth mother, who would have been no more than eighteen. She wanted a say in who would adopt him, and a wise social worker thought she had that right. That young girl trusted him to to a couple not that much older than her. She will be in her sixties, now.

It’s a complicated story, but the core of it is that we were at yet another stage of the usually ponderous adoption process, which suddenly accelerated quite wonderfully and frighteningly, and we found ourselves sitting in the small living room of a foster-mum, and our David, who wasn’t yet Our David, four months old and surrounded by love, was having his bath. He wasn’t called David, either. He was Conrad Hamilton Gervaise Irving (no surname), and just Conrad, for convenience. When you adopt a child you’re not supposed to keep his or her given names. Since the truth is that the amazing and enlightened social worker short-circuited every due process that evening, and that we drove home up the M1 with Our David in a carry-cot on the backseat of a Ford Anglia, it didn’t seem so transgressive to keep Conrad as his middle name. David Conrad Foggin.

This much

I remember:

the small neat creases, the crook of each elbow,

the crook of each knee, the soft place

between your neck and your shoulder,

and the tight whorls of dark hair

tattooing your skull, and the delight,

the wide pink of your open mouth

as you came shedding light and bright water

out of your bath, how you sank

in the fleece of a fat white towel,

and you lay on your back on her knee

and you danced,

how you pedalled and trod on the air,

and how pale the soles of your feet.

You were mangoes, grapes, you were apricots,

all your round warm limbs, your eyes.

How your name made you smile;

how we said it over and over, your name;

how we wanted to make that smile.

And I remember

how we would take you away,

and why your name could not come,

why we must leave it behind,

and how we feared for your smile.

When his face would cloud over, or when he seemed to turn inwards (as happens with all your children) it troubled us. And then it would be OK, and we’d forget.

Later, when he was nine or ten years old, he drew endlessly; meticulous battle scenes, some times on rolls of lining paper, so they stretched out like eclectic Bayeaux tapestries. I wrote a poem about them, years ago, and keep revisiting it, and rewriting it.

Our David’s Pictures

In tracing the anatomy of war

our david’s concentration’s absolute.

He kneels in peace, head bowed. An acolyte.

His pictures conjure tiny armies on the floor.

All history’s invited to this fight:

Martello tower, pele, and launching pad,

heaps of Roman, Norman, Saxon, Panzer dead.

Drawn up, his minute cohorts. Black and white.

Each man’s accoutred – breastplate, chainmail, greaves.

Crusaders squint down Gatling sights,

or brandish spears with blades as big as axes,

and quivers jammed with arrows, bunched in sheaves.

Every shield’s a wicked chevron

or a bossed and studded disc;

the sky is bristling with a stiff cheval de frise

of arrows and everyman’s vulnerable, at risk.

There’s Agincourts of arrows, flight on flight.

The sky’s cross-hatched, and somedays almost black.

The sun’s crossed out. Eclipsed. Our David’s arrows –

they fly miles, out of day and into night,

they shift the whole perspective. What is it

he celebrates? Pattern? Power?

The living or the dead. I’ll never know,

his last bow drawn, and loosed, an age ago.

I wrote this when he was still alive, puzzled and perhaps mildly worried about the obsessive quality of the drawings. But mainly delighted. When he died, I changed the ending, and it was read at his funeral. We had a Bob Marley track in the service. Stop that train. It was an extraordinary service. There were dozens and dozens of young people who I’d never seen before, who I didn’t know, but who had clearly loved our David. For some reason he either never knew, or if he knew, he didn’t believe it.

It was a long time between being told of his death and his funeral. My wife and I had separated seven years earlier. We weren’t asked identify his body and I was too numb to wonder why I wasn’t notified of the inquest, and I was too numb to protest. The morning the police told my ex-wife of a death behind the Merrion Centre, the morning she drove from Leeds to tell me, the morning we went to the police station in Chapeltown was the morning I started to learn about the lovely boy I realised I didn’t really know. That he’d been smoking dope, that this may have triggered a suspected schizophrenia, that some time earlier he’d served a short prison sentence for a trivial non-violent offence, that he was being looked after by NACOS, that he was training as a painter and decorator (like his great-granddad). I know I could have known all this, and I should have, but I was too busy, too tied up with a new job, a new relationship, and deep down, because I was scared to ask. Most of those young folk at the funeral were young offenders on schemes like the one our David was apparently enjoying. Nothing made sense.

It was a morning like this

a Sunday morning. The sun shone.

It was July. It was a morning like this,

your ex-wife at the back door,

and why would she tell you

your son was dead, or had died,

or had been in an accident

on a morning like this still

not fully woken, a morning of sun

to drive into Chapeltown to drive

to a police station that’s called

The Old Police Station now, that’s

a bijou gastropub but then was just

a police station full of Sunday morning

sadness, and a morning something

like this and two young coppers

who thought we’d need somewhere

quiet at the back which turned out

to smell of smoke, that had a pool table

and coffee rings, and no-one knew

how to start or what to ask but

it was a morning much like this

they asked if we knew a tower block

behind the Merrion Centre or if

we had a connection to a tower block

and a ring with a skull and a brown

leather case and did we know if

our son had friends in a tower block

behind the Merrion Centre and

we might as well have been asked

about tree rings or chaos theory

or fractals on a July morning and

one young copper saying that

he didn’t think it made sense

for cannabis to be illegal and

what harm did it do really and

how it wasted everybody’s time

and I don’t know why I’d remember

that except it was a morning like this

I learned what waste might mean.

A couple of weeks after David’s funeral my good friend Bob Hogarth, the Art Adviser said: why don’t you do a painting of him? Why don’t you paint his life? I set out on a collage of maps of the city, photographs of his childhood, images of a small attache case and a strange ugly ring that he’d left on the top floor of that block of flats behind the Merrion Centre, an old atlas open at a map of Africa. Buddleia. Hydrangeas. I worked on it for a week or so. And then stopped. Just a layer of collage and thinned down acrylics. Every couple of years I’ll have a look at it, and resolve to finish it. But I don’t think I want to. I suspect I understand why. It took a long time…more than twenty years…to find out that for me the answer lay in writing. Maybe it started with a friend of a friend buying me Jackie Kay’s Adoption Papers, and then started again with being told about Carrie Etter’s Imagined Sons.

It started with rediscovering Greek myths, and particularly the story of Icarus. It was discovering, through the process of retelling the story, that the character no one pays enough attention to is Daedalus, or points out that if Daedalus had used his amazing gifts well, he would never have needed to build a labyrinth, would not have given away its secret, would not have been imprisoned in a tower with his son, would never have needed to conceive of making wings. I understood, through this that if you make wings for your children, it’s not enough to just watch them fly. Whether they fly into the sun or the heart of darkness, if they fall, then are you responsible, and how will you live with that.

Tony Harrison wrote that in the silence that surrounds all poetry

‘articulation is the tongue-tied’s fighting’ .

I believe articulation is healing, a way to atonement and to being able to forgive yourself. The serenity to accept the things you cannot change. Articulation can be confessional, too. You can’t change the past; ‘what ifs’ and ‘if onlys’ simply make you spiritually ill. We know this, rationally, consciously, but living by it needs help. Two poets have given me that help. Clare Shaw’s credo “I do not believe in silence” and her unwavering frank gaze at her history of self-harm, and psychological disturbance gave me courage. As did Kim Moore’s decision to use poetry to deal with her experience of domestic abuse. And, finally, one moment in a writing class that Kim was running that somehow unlocked suppressed and unarticulated belief, guilt, knowledge. I remember I wept silently all the time I was writing. It only lasted five minutes, that task. But an insight, an acknowledgement takes only a moment no matter how long the process that leads up to it. This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine says Prospero at the end. I think I understand the release he must have felt in that split second.

A weak force

there’s sometimes a loss you can’t imagine;

the lives never lived by your children, or

by the one who simply stopped

in the time it takes

to fall to the ground

from the top of a tower block.

They say gravity is a weak force.

I say the moon will tug a trillion tons

of salt sea from its shore.

I say a mountain range will pull a snowmelt

puddle out of shape.

I say gravity can draw a boy

through a window

and into the air.

There is loss no one can imagine.

In the no time between

falling and not falling

you learned the art of not falling;

beneath you burned

the lights of Sheepscar, Harehills,

Briggate, Vicar Lane;

lights shone in the glass arcades,

on the tiles, on the gantries of tall cranes;

motorway lights trailed ribbons of red,

and you were far beyond falling.

Because you shut your eyes

because you always shut your eyes

you closed them tight as cockleshells

because when you did that the world

would go away the world

would not see you.

I remember how you ran like a dream.

I remember how you laughed when I swore

I would catch you.

Then you flared you went out

you flared like a moth and you blew

away over the lights over the canal

the river the sour moors the cottongrass

the mills of the plain

and over the sea and over the sea

and the bright west

and you sank like the sun.

I count myself lucky. Lucky to have had our son for 21 years. Lucky to have learned to live with the loss of him and to have learned how to make amends to myself and to his memory. Lucky to be able to articulate it.

This week we learn we now have a Minister for Suicide. She has no budget, no staff, no office, no brief. A disproportionate number of young men will take their own lives in the coming year. Some of them will have been made desperate by being stripped of benefits, being made homeless; some will have been denied the recognition and appropriate treatment the desperately need for their mental health issues. Whatever their circumstances, there will be parents, siblings, partners, children, friends who will be numb, full of unassuageable guilt. There is loss no one can imagine.

Beautifully articulated, John. As ever, I’m sorry for your loss, I was thinking of you on World Suicide Prevention Day xxx

LikeLike

This will resonate with so many people, John. Thank you for sharing such a moving, personal story.

LikeLike

Heart-breaking, devastating. My grandfather, who had said I understood him better than anyone else did, committed suicide when I was 16. xxx Hilary

>

LikeLike

What a moving, beautifully written post, John. All love to you. Xxx

LikeLike

articulation healing, yes, thank you for sharing this!

LikeLike

Thx for sharing

LikeLike

Your post touched me enormously, John. Thank you for sharing it, and your poems.

LikeLike

Take you. That means a lot xx

LikeLike

This was very moving. I

lost my niece to suicide three years ago. Supporting my sister and all my family is a life-long journey. Love and understanding even though I don’t know you. Louise xxx

LikeLike

Such love and beauty from such pain xxx

LikeLike

John – I remember sitting in your 6th Form class and hearing you tell us about the imminent adoption. You were sitting on a desk and glowing with excitement, and so happy. And yes, I even remember the Ford Anglia. And all that now a lifetime (literally) ago. How can a life have been lived and ended since then? But yes – articulation can be a comfort, not to say a compulsion. When things looked bleak, my father used to say: “Remember, there’s always poetry.” Jean x

Jean Sheridan Mercury, 2 Southgate, Helmsley, York YO62 5DA 01439-772388 jean.sheridan111@btinternet.com Secretary, 1812 Theatre Company Helmsley Arts Centre, The Old Meeting House, Helmsley, York YO62 5DW

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m feeling very guilty about not having answered this immediately, Jean. It took me back so many years to where I was happy not least because I didn’t know any better. Which is actually the only way to live, I suspect. Thank you for that memory xxxxx

LikeLike

Thank you John

28 years ago this week that my husband took a step to wipe out the world that made his existence unbearable ( whilst I revelled in the late autumn sun at bretton)

LikeLike

How good to hear from you. I’m moved and astonished by the responses I’ve had to this post…I had no real idea about just how many lives have been thrown out of kilter by this issue, how deep and wide the desperation and grief. Much love. Be well and go well xxx fogs

LikeLike

Very beautifully written and very touching. I found a lot of comfort and understanding in your post. I am going through the loss of a loved one who took his own life in September. I find myself still going through so many emotions, questions, thoughts. Thank you for writing and sharing your story.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing. I am so sorry for your loss. All I know is we have to share our stories. Go well, be well xx John

LikeLike

John, I re-read this today. I know this loss never stops. I am so sorry. There is always poetry but no David. ( I remember your telling me about his original name Gervaise which seemed so extravagant for a tiny baby.) In Northern Ireland we have had a very high suicide rate since the Troubles ended. Usual multiple causes, they say, and every small town has its suicide prevention club full of the bereaved. Teachers are aware that this is something that has affected every class they teach, through family and friends and neighbours. One of those things where not praying, for an atheist like me, does feel hard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me…an atheist, too. And I say prayers. I think of it as talking to a better self xxxxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person