[This post was originally published on the Write Out Loud website in September]

.

I read this on Julie Mellor’s poetry blog last week: “I aim to post something once a week on my blog but last weekend I skipped it. Maybe I didn’t have anything to say. Maybe I didn’t have the energy or drive to write it. Anyway, I thought I’d better get on with it today before another weekend slipped by.”

Me too, I thought. Me too.

And then I read this in Anthony Wilson’s Lifesaving Poems: “If you write poetry (and I assume that if you do, you are also actively engaged in reading it), sooner or later Poetry Exhaustion is going to happen to you. By Poetry Exhaustion I mean the complete lack of that shock of recognition you’ve always been able to count on from a favourite unputdownable book of poems. Or the sudden knowledge that the poems you have been working on for the last two months are certainly not your best work and actually not even worth keeping (though you do, in case).”

It sums up exactly the kind of ennui, mental blankness that’s stopped me writing posts and reviews and poems. It happens. You just have to hunker down and wait for something to change you. Like a poem, you can’t just will it into existence.

Last week, out of the blue, I decide to re-read Robert Macfarlane’s The Old Ways. And suddenly, phrases come jumping off the page, .moments that get you in. Phrases like these:

The cold like a wire in the nose.

Snow caused everything to exceed itself

starlings…feathers sleekly black as sheaves of photographic negatives

big gulls…monitoring us with lackadaisical, violent eyes

a dolphin….a sliding bump beneath the water..like a tongue moving under a cheek

star patterns..the grandiose slosh of the Milky Way

gannets bursting up out of the sea…like white flowers unfurling…avian origami

[and, after a hard long hike] … feet puffy as rising dough

It was lovely. Language well-wrought can galvanise you like that. I’ve had a review waiting to be written for months. Macfarlane let me know that it was time I got on with it.

When I started my first poetry blog, the great fogginzo’s cobweb, I wanted, among other things, to publicise the writing of poets who fly under the radar … the ones without a ‘book’. I quickly learned that most of them were not ‘undiscovered’ at all. They just weren’t self-publicicising. They had been published in respectable and reputable magazines. They had won prizes. They just didn’t go on about it. They didn’t have a collection. They didn’t particularly do open mics, or get guest reader slots. But they couldn’t half write. At least as well, and often, I thought, a good deal better, than some published poets. And such are today’s poets, Vicky Gatehouse and John Paul Burns, both of whom I keep meeting at the Poetry Business, or, by accident, at open mics and readings.

I should add something else. You go to writing and critiquing workshops and you become aware that you’re hearing a poem and a poet, in the process of becoming: Kim Moore, before she won anything, before she had her first pamphlet, trying out the first draft of her ‘Train ride from Barrow to Sheffield’; ditto Roy Marshall with a draft that had echoes of Heaney; Julie Mellor, also, with a mole on the neck that marks you for hanging; Keith Hutson and a suicidal, drunken pantomime dame. It’s like seeing a musician before s/he becomes a star. Like seeing a 16-year-old Ginger Baker drumming for Terry Lightfoot’s band in Bradford. Which I did. Or Dylan going on the open mic for the first time in Greenwich Village. Which I didn’t. I’ve added today’s poets to the list. They couldn’t be more different voices.

John-Paul Burns

Kim Moore writes of John-Paul Burns’ poems in The minute & the train that “the speakers in these poems are often out of sight, looking outward at landscape, objects or people while using clear-eyed and precise descriptions … leaving the reader with the realisation that looking out can also be a way of looking in”.

I think of Isherwood’s “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.” I think of a kind of attentive detachment, a sort of separateness, like Stephen Daedalus’ willed secrecy/invisiblity. I also think of the Larkin of Mr Bleaney. It’s like being in a land where we are in the shoes of a traveller, and outsider. There’s a shared anonymity, that of the observed and observer. It’s no accident, I think, that John-Paul’s first degree is in film, that the films he references include silent classics, and that the jazz he references is ‘cool’. It’s not accidental that the poems are monochrome, and mainly silent when they’re not quiet.

A first fast reading through the pamphlet left me with the impression of particular times: night, twilight, sunrise; of bedsits, and shared houses, (like Mr Bleaney muttering to his younger self); urban places, the corner shop, the old factory, a lot of reflecting rain, almost unpopulated landscapes, gravestones, rags, odds and ends fragments, exhaustions:

My hair is brown, dark to the point

of black when rained on. It blocks the drain

as everything does (‘Drinking Songs’)

It also left me trying to figure out the fact of apparently random or wilful line breaks, indentations, capitalisations. I’m still not reconciled to those, but repeated readings override the initial sense of alienation in distressed places. Something much more committed, engaged and human, and sometimes funny, is going on. The most obvious is that though much of the work is studiously monochrome, it can explode into an unexpected and startling colour.

you’re all belly aren’t you

everything is patches really

intimate as waxwork

A suggestion of planet in the pool.

of orange moon. (‘A tangerine being drawn’)

or in a later poem, the moon again “as it meanders from orange to pink”. There is “ruby ale, lovely blue grass”, and in ‘Cricket club scene, Oldham’ a flood of colour: “a deep yellow hour. / The red ball, a deep ochre red; / pale violet rooftops /orange-green parakeets”. Considered and precisely Technicolor colours, that have the impact of the Tecnicolor sequence in that 1949 film The Secret Garden. Here’s a poet who knows just what he’s up to.

In her review in The High Window online quarterly poetry magazine recently, Carole Bromley wrote: “As far as subject matter goes, Burns is particularly good at capturing the world of bedsits, shared flats and houses. I get the feeling that the poet in him longs for solitude, while the young man with a sense of humour can enjoy company, parties, drunkenness.” She adds that he is also “an observer with a gift for capturing landscapes, objects and people. A pear “waits for the hand/that will hold it, give it/its pear shape, bite into/its sweet and dripping self”, a tangerine “will be torn without violence/ Your oils will mist a fresh sweat into the air/ You will disappear and you will remain”, at a cricket club “The track curves in the grass/ with no-one running. They play/ just out of earshot, a deep yellow hour.”

What I’d add to this is that his urban and rural/coastal landscapes, both interior and exterior, can be sinister and disturbing in the way of Expressionist cinema, as in the decidedly unsettling ‘Knott End-on-Sea’ which incidentally also illustrates what I think is an arbitrary use of capitals and indents without punctuation. I can be open to persuasion on this.

The footprints trail off out of sight

The sand stays in the morning

A pale blue dusk sitting above it

And Jimbo the dog is missing

Out beyond the soft horizon

The man in the footprints exhales

The narrator is apparently looking out of the window of a cafe on a nondescript bit of shallow coast, making notes, or planning a storyboard of something Hitchcockian, and with the relish for the suggestion of menace in its ambiguities, the questions it asks, that infuses that one word “exhales” with something troubling.

I want to finish, though, on what I said earlier about the engaged, the warm, the human that runs through the studied stance of ‘attentive detachment’. Take this, for example:

A bundle in the mist

When I think of the arctic terns

they come in pairs from years ago

flirting over the stones in the wide teal

of Shetland air.

Let me have them as they seem.

Allow their blurriness too, swerving up

from the name Shetland with faint high knells.

There were no bells, but further in

there are.

Say the word and the birds come, chiming.

I could live for a while in one spark like this

I love the wholehearted openness of it, the undefended credo that ends this sequence; it’s epiphanic, like Stephen Daedalus standing on the shore, every nerve singing to the joyous otherness of things.

And finally, a poem that Carole Bromley also highlighted:

Two views of Whitby Harbour

One by day, bright for October

and calm. I say it’s strange really

and you laugh: the giant Doric column

bitten by the salt wind

that is absent today. Cormorants

line the Eastern Pier

crooked, athletic and shy.

The sky is a flat sky blue

Another by night, sharp

and calm, though the wind

picks at the black ocean skin.

A creaking hinge; the night-

fishermen cast in silence.

Vague white seabirds hover

dashing at the air;

there is no horizon.

I like this for the way it evokes an unforced, easy companionship, a happiness. The ‘I’ and ‘you’ are abstract but still seem specific as the moment is specific, and the cormorants are memorably recorded: “crooked, athletic, shy”. Surprising and true. A moment that gets you in. I like the wry humour of “The sky is a flat sky blue.” I like the creaking hinge that is sort-of-lifted from Robin Robertson. I like the way the birds are vague and sudden at the same time, batting at the mist to simply stay still. It’s a poem that’s worth the entrance money on its own, in this genuinely interesting first collection that will stick in your mind for a long time.

Victoria Gatehouse

And so to Vicky Gatehouse and The Mechanics of Love. I said they were strikingly different voices. Other reviewers have made much about the fact that Vicky trained as a scientist, but I’m not sure they quite nail down what it means for the poems. I may not, either, but we’ll see. Gaia Holmes identifies what I think of as the exuberance of the collection which is full to the brim with “love locks, 1980s perfume ads, cross dressers, owl pellets, pearl divers, Premier Inn hotel rooms, the visceral trials of a lab technician, lost tennis balls, spiders’ webs, the delightful idiolectic ‘Shunkley’ and the speakers’ ‘magpie need for bling’. ”

Vicky Gatehouse is pretty much always the actual voice of the poems, which are more often than not autobiographical. These are poems populated by identifiable people: mothers, grandmas, husbands, younger selves, biology teachers, and abattoir man in a bloodstained apron, mum’s friend Sylvia; like the cross-dresser in Lenton Boulevard, they live in identifiable places like the Premier Inn or the Pont des Arts, and are surrounded by artefacts and goods with resonant names: Aartex, Midget Gems, Poison, Fortune-telling Fish.

Gaia also identifies what she calls “the muscular language of the heart”. Vicky Gatehouse’s poems involve physical as well as emotional engagement, and her imaginative memory is tactile as well as visual. She is as concerned and slightly anxious for her earlier adolescent self as a mother. I would be inclined to say that that is normal enough, and possibly not enough to lift the poems out of the run of enjoyable, competent poems we write about ourselves. What makes the difference, I think, is the science, the combination of exact and intuitive knowledge of how the world works, its structures, its mechanisms. The whole pamphlet challenges the popular elision/confusion of mechanism and mechanistic with its secondary connotations of dehumanisation and the binary opposition of mind and body. What I like (and hope to demonstrate) is the understanding in the poems that knowing how things work doesn’t take away their wonder, but actually intensifies it.

When I think of ‘the mechanics of love’ I think of UA Fanthorpe’s ‘Atlas’, the kind of love called maintenance that knows where the WD40 is. I think of mechanics as a set of abstract principles, and also as people who mend and put things to rights. Doctors, for instance. And mothers and fathers, and lovers.

I’m inclined, therefore, to disagree with Mat Riches’ review in Sphinxwhen he writes that “Starting with the perfumery of ‘Poison, 1986’, and the ‘Sixth Form Science Technician’ being sent out to collect supplies for student experiments, science leaps out of many of the poems…”, that “as a result of having a day job in medical research – these poems take a microscopic look at love and life as though they’ve been carefully sampled on a slide and Gatehouse is noting the beauty and fragility of the findings.”

I don’t think they’re as calculated or as forensic as this suggests, but rather that scientific language and thinking comes naturally as part of her ideolect and way of experiencing things. I had much the same take on Emma Storr’s Heart Murmurs [Calder Valley Press 2019], a poet who naturally thinks like a doctor because she is one. This makes it different, I think, from the way poets like the Metaphysicals and some modern poets bring in ’science’ as it were from the outside. Indeed, Vicky makes the point herself in ‘Fortune telling fish’ when she says

A scientist now, you could explain

that whisper-thin strip as hygroscopic –

swelling or receding with the level

of moisture in the skin

She’s pointing out that this doesn’t explain the fact, signalled by a “but” that “you’ll find yourself wanting to show” you’re passionate, or independent or whatever, and science won’t explain that. Not at all. I wrote in another poetry blog about her poem

The moth

This is her time –

birds dark-stitching telegraph wires,

the woods blue-shadowed,

crackling with dusk.

The moon untethers her,

she pitches from fence to wall

to leaf, would hurl herself

for miles, such is her faith

and you think of how she gorged

on hawthorn and thyme, spun

herself a mantle, hung tight

inside the blackout

of her own skin

before the breakdown, the forcing

of all that remained

through the veins of her wings,

this lit-bulb junkie,

wrecking herself on your porch light.

(Ink, Sweat and Tears, 2015)

I really get a buzz from the controlled energy of this, and the way images imprint themselves (“how she gorged / on hawthorn and thyme.”) “Gorged” is absolutely spot on and surprising. And “the blackout of her own skin” is rich and layered. Blackout curtains, fustian and dusty; blackout unconsciousness …a binge-drinker’s blackout that springs the trap for the ambush of “this light-bulb junkie”. You can read and re-read this and it keeps on giving. I’ll go on highlighting the fact of energy, the accurate richness,of her language. This new collection is packed with the moments that ‘get you in’, often in opening lines like these

The biology teacher wanted blood

I remember kitten heels clipping tarmac

It ticks me to sleep,

the titanium valve in your heart

On the fifth day I find it in your cot

There’s a specific narrative in each of these which I immediately want to hear, to have explained. And the poems never let me down. For instance, what we find in the cot is the shrivelling umbilical cord that had

… pulsed between us, blue-white

vigorous, the best I had to give –

stem-cell, lymphocytes, streaming

down the line they had to cut off.

There it is. The physical immediacy as intimately known as what the cord actually did, when it pulsed, blue-white. I like that word pulse. That’s what so many of these poems do, as she explores her memories of adolescence, the mysteries and excitements of burgeoning sexuality; also the memories of becoming and being a mother, a wife and a lover, a daughter. She finds an emblem for all this textured experience in the opening poem, ‘Inosculation’:

And this will be no perfect union

but one born of abrasion: two trees

grown close enough to graze, to chafe

as they shift in the wind, their bark worn thin

The title is a label for a process, but the poem in its crafted consonality enacts the process itself. It’s not an idea but a felt experience. And it’s lovely. Gaia Holme’s endorsement should give you a taste for the tumbled richness of things in The Mechanics of Love. I’ll finish with a poem that might seem a surprising choice, but which, I think, tells you what’s at the heart of Vicky Gatehouse’s collection. On one level it’s simply a beautifully observed set of moments that come like “talons trailing the tips of the wheat, to the tooth-hole ruin of that barn”, (THAT barn, notice); on another you might call it Birth of a Naturalist. It’s the moment you go back to, again and again, it’s a rite of passage. It’s as exact as the “dark, neat parcels of feathers and fur,/ the pale curve of bone”.

Pellets

This is the hour when she thinks of the field,

the unsteady embrace of drystone walls,

end-of-summer grasses, whispering

their untidy truths, the tooth-hole ruin

of that barn where she first found the pellets –

dark, neat parcels of feathers and fur,

the pale curve of bone within, each one

packaged up like a gift so she had no choice

but to return every evening, at owl light

and wait for that change in the air, the weight

that comes on silent wings, talons trailing

the tips of the wheat, a half-lifetime ago

and still the bleeding, unseen beneath the gold,

the skeletons in her pockets, carried home

It’s also unnerving; a poem about a compulsion that remains after half a life time, where whatever else has happened, there is “still the bleeding, unseen beneath the gold, /the skeletons in her pockets, carried home”.

There we are. Two pamphlets that couldn’t be more different, and which both will hold your attention and fix themselves in your minds.

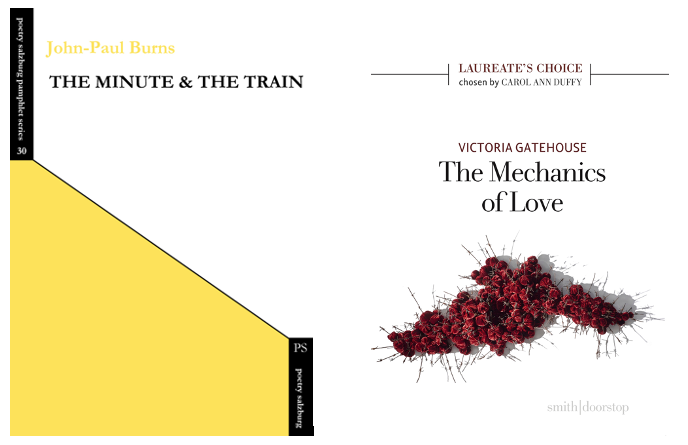

John-Paul Burns, The minute & the train, Poetry Salzburg, £6

Vicky Gatehouse, The Mechanics of love: a Laureate’s Choice, Smith|Doorstop, £7.50