.

.

I’m ever so grateful to The Friday Poem, and to poet Maryann Corbett for permission to use extracts from Maryann’s poem Erasures. It’s about the necessity imposed on the librarian to periodically cull the shelves of unread books

What he remembers is the poetry.

The graceful little books, a hundred-some

years old, the 1890-to-1920

range. Some leather-bound, some with gilt edges.

Elaborate end-papers, ribbon markers,

physical richness no one pays for now.

…………….

Scanning the cards and date slips, he considered:

Sometimes a given book had four or five

names, neatly penned in its first year of life,

a flush of bright attention. And then nothing.

Mostly just one — a friend? a family member?

One name. There followed decades of no interest,

he writes forlornly.

……………..

Erasing them was not what he was doing —

not he, nor shredders, nor incineration.

Indifference had erased them.

.

[For the full poem, just click on this link. https://thefridaypoem.com/erasures-friday-poem-corbett/ ]

Well that struck a nerve. I’ve been mulling over this post for a while, and then, via my friend Hilary Elfick, The Friday Poemoffers me a perfect starting point. You’ll see why as we go along.

It all starts with my looking at the stats for the cobweb and realising that, after about 460 posts since 2014, I’d amassed over 750K words and suspected that most of it was either redundant or unsearchable. I spent a day scrolling through and culling about 160 posts…most were duplicates/reposts, some were time-expired and of no more interest; some were simply dull or ill-advised. What struck me, however, was that there was an archive of guest poets who were all worth revisiting.

What the cobweb needed was an index. There are 100+ guest poets, and some have appeared two or three times. But there’s currently no simple way of finding where they are. And then I decided that I could also do something (anything!) about promoting my own stuff, apart from the bit where you can press Paypal buttons to buy stuff. And I needed to update the autobiography. And so on.

When I started to look at some of the very early posts I found that many of the images I’d used have vanished…time-expired…so those would need attention. I don’t know how long it’ll take, but I simply have to take some time out, and knock the blog into some sort of usable shape.

So much, so simple. But there’s more to it. Basically, if you want to maintain any kind of credibility as a poetry blogger, you need to be engaged with the world of poetry, who’s in, who’s out, who’s on the way up, where’s it all going….and so on. And for all sorts of reasons, I’m not, if I ever was. So long as I was jointly running a monthly poetry event, so long as I was getting out and about and blagging guest spots at other poetry clubs, so long as I was regularly getting to readings, to writing workshops and residentials, so long as I was doing that I was meeting poets of all kinds, listening to new voices, buying books. The whole nine yards. Tiring but exhilarating and battery-charging in equal measure.

And then along came the double whammy. The pandemic locked me down, and then various cancer treatments that affected my immune system threw away the key. Yes, I’ve been kept sane by regular Zoom workshops with my mates at the Albert Poets, and by Zoom courses with poets like Kim Moore and Jean Atkin. But the buzz isn’t the same, and above all you miss the accidental encounters and conversations that surprise you into creativity. Apart from that, not travelling, not seeing changing landscapes, new faces …it all dulls the imagination. Basically, I’m tired and unresponsive. I got to a point where I couldn’t think clearly or quickly or sharply. And I don’t think I’ve been doing my guest poets justice. That’s one thing. As to the other, I need to resort to analogy (always a danger sign).

.

Remember “Q” magazine. There was time in the 90’s when I couldn’t be without it. And then I couldn’t be bothered with it any more. It was always the ‘next big thing’, the next ne plus ultra. It was all summed up by the page after page of reviews of releases by bands who I’d never heard of, and were all amazing and unmissable. There wasn’t enough time in the world to find if the reviews were true. We were drowning in a plethora of latest things. So I gave up. I couldn’t keep up any more. It’s like reading James Ellroy (American Tabloid et al)..you know that the characters are genuinely interesting, that the plot is pacy and complex, but the prose in all its telegrammatic density is utterly exhausting. It’s like being bludgeoned. Here’s another parallel. I’ve recently been reading ..or trying to keep up with…Nicholas Crane’s The making of the British landscape. It’s genuinely interesting but it’s also the prose equivalent of timelapse film. Continents slide, icecaps rise and fall like meringues, a huge chunk of Norway slides into the abysmal deeps beyond the shelf and a tsunai takes out Doggerland. Forests multiply like bacteria and shrink as suddenly. You’re conscious of convulsive change but the timescale becomes incomprehensible. It’s all too much.

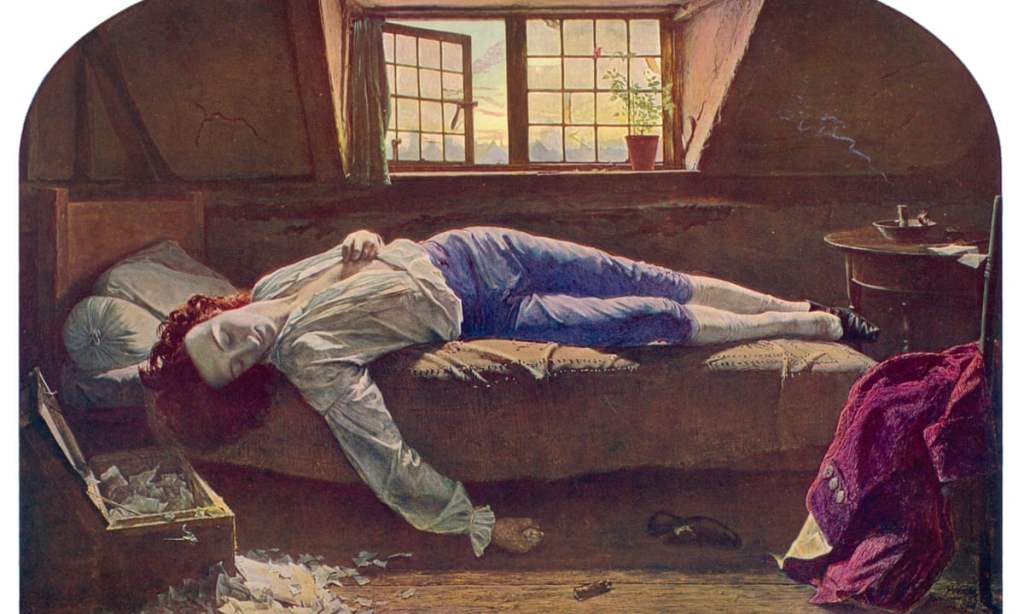

And, that, gentle reader, is just how the contemporary world of poetry seems to me. It’s a full time job to keep track of it, and for much of the time (as with those groups of the 90s that never went anywhere) it doesn’t feel as though it’s worth the effort. In a dark mood I’m inclined to agree with Clive James’ view that there’s never been a time when there’s been so much Poetry about and so few real poems. Social media is dense with folk announcing that they’re ‘working on their new collection’ five minutes after the last one came out, or folk posting pictures of their recently arrived books fresh from the printer. I should know. I’m one of them. I also know (and I’m not surprised) that my second collection came out in May and vanished without trace. As far as I know, it’s not been reviewed. Why should it be? I’m not getting to poetryt events where it can be heard. There’s a tsunami of new pamphlets and chapbooks and you’re either surfing the wave or you’re overwhelmed. It is what it is. But I really do want to stand back and reconsider where to go next, if at all. I want to clear my head. I want a rest.

So. I’m signing off for an unspecified time while I curate the great fogginzo’s cobweb and make it fit for purpose. When I come back I’ll want to be sharing enthusiasm and clear-mindedness. There are poets who I know I want to write about. But not till I can do them justice.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with extracts from a post I wrote some years ago. It’s about hope and ambition, both realistic and unfounded. In one way and another it seems relevant. As does Maryann Corbett’s poem. (see what I did there?)

The post is from 2016: So you want to be a rock ‘n roll star

.

“In the last year or so, I’ve reviewed – or blogged about – collections that I love. Kim Moore’s The art of falling. Christy Ducker’s Skipper.Fiona Benson’s Bright travellers.Jane Clarke’s The River.Work by Shirley McClure, Maria Taylor, Hilary Elfick, Tom Cleary, Bob Horne, Steve Ely, Clare Shaw, Wendy Pratt…loads of them. I’ve been asked to read manuscripts of draft collections and wished they were mine. I just signed a contract for a first collection of my own poems…of which more in another post. And I’m involved in a frustrating email exchange about the cover design. “

(that was how it felt, to be involved. The past is another country!)

“We can all dream. Write poems. Get them accepted by The Rialto, Magma, Poetry Review...all of them. Find a publisher. Bloodaxe would be nice. Get great reviews, prizes. Sit in Waterstones and sign copies as the queue stretches out of the door and along the street. We can dream, and so we should; our reach should exceed our grasp, or what’s a heaven for? So.

.

You go on writing, and maybe you get some poems accepted by magazines. And for a bit you feel sort of content. And then folk start asking: have you got a collection out yet? And you look at the growing files of poems you’re more or less pleased with. Your ouevre. And that ‘what shall I write about?’ morphs into ‘when will I be published?’. More specifically, ‘I want a collection’. Which morphs into ‘When will I be famous?’. And then poet-envy. Then doubt. Despair. Oblivion.”

“Everyone’s route to a collection is different. ( I nearly wrote ‘journey’ and caught myself just in time). This was mine………..

Years ago, I did a part-time Creative Writing MA. To be honest, I really did it because I was semi-retired, and struggling to cope with free time. I thought that committing to a course would put some discipline into my life. It didn’t, but that’s another story. On the other hand, I was struck by the diffuse ambition of my (much younger) fellow students. None of them asked questions about how to make their work better. But they constantly asked about how you set about getting published. I didn’t get it. I genuinely thought it was hard enough to actually learn something about the craft of writing, and to actually write some poems.

But. I’d got a taste for it, even if I didn’t acknowledge it. It was Poetry Business Writing Days that set my feet right. You learn from the company you keep; I was taken along for the first time by Julia Deakin, to whom I shall be eternally grateful. I sat in rooms with people who seemed to write as though writing, and getting it right, was enough. I was comfortable in their company. Eventually, though, the conversation would turn to magazines and pamphlets and collections, and I realised after all that just writing better wasn’t enough. What was the point, if no one was reading your stuff?

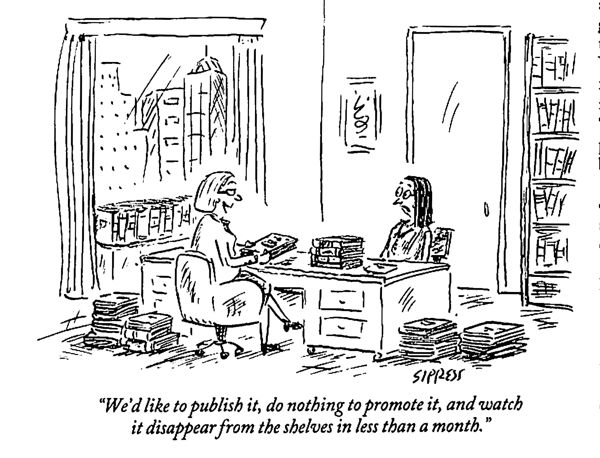

Why would they would be reading yours? Who would notice? How would they find it in the multiverse of books and bookshelves and libraries and bookshps? I remember saying to Ann Sansom that I couldn’t see why folk would pester publishers. Or why poetry publishers put themselves through it. There’s no money in it for anyone, that’s for sure.

.

Something that’s stuck in my mind since then is an anecdote that Simon Armitage put in his account of walking the SW Coast Path and reading at various venues along the way. (Walking away.Faber). He’s staying overnight at what was the home of Peterloo Poets…who, inter alia, were the publishers of U.A.Fanthorpe. At some point, they simply went out of business. And left behind thousands and thousands of unsold copies, gradually falling prey to dust and damp. There you go. No one’s going to see your stuff on those crowded shelves, and eventually you’ll be remaindered or pulped. It’s a profoundly depressing thought.

(But as it turned out, I’ve realised I’ve been lucky enough to sell up to a 100 copies of some the books I’ve had published. The flip side is that I probably know everyone who ever bought a copy. I guess that when you’re selling books via bookshops, and strangers are buying them, then you’ve started to make it. )

“You send stuff out, you enter competitions, you do open mics. You realise (well I did) that even if someone offers to publish you, it could be over a year before anything happens. And maybe you think you haven’t the patience for it. That’s what I felt like, but at the same time there’s something deeply unsatisfying about a whole bunch of poems that sit there in their Wordfiles, that have no physical heft. As it happened, still struggling to cope with semi-retirement, I enrolled in a bookbinding course at the Tech in Leeds. Learned very simple techniques.. Decided that for my assessment projects, I’d make books of my own poems. So I did.”

(later I went in for self-publishing, just so I could have multiple copies to sell (hopefully) at open mics and so on

“You want to be published? Just do it. Two of my happiest memories are seeing the big smiles on the faces of Kim Moore and of Jane Clarke when their brand new collections came out.”

(in 2016 I must have thought the world was my oyster; I wrote this:)

“I started off by making handmade books, just for the fun of it. Then I got a printer. Then I won a competition. Then I won another. I’m a lucky boy. My first collection’s coming out in November. I may even post pictures of it. Or, like Jane Clarke, go to sleep with it under my pillow. You’ll never be a rock ‘n roll star. That’s not what it’s about. But whatever you do, just do it. You know you want to.”

I was going to sign off with an ironic flourish :Hasta la vista. But someone just trashed that for all time. I’ll stick to something more low-key. I’ll be back.