.

“There are maps of a kind…but the trouble is, the maps are always last year’s…..England is always remaking itself, her cliffs eroding, her sandbanks drifting, springs bubbling up in dead ground. They regroup themselves while we sleep, the landscapes through which we move…the faces of the dead fade into other faces as a spine of hill in the mist”

from: Bring up the Bodies

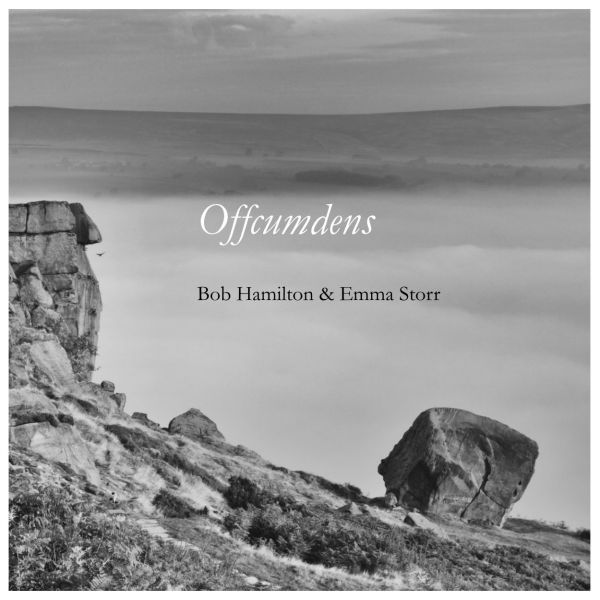

This, for me, is one of the most memorable passages in the cornucopia of memorable passages that is Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, and it explains in some measure the urge that lies behind Bob Hamilton’s and Emma Storr’s Offcumdens. At the heart of it is that phrase

the landscapes through which we move

It’s the idea that landscapes are never static, that they change moment by moment and aeon by aeon. They change because we move through them,and they depend on viewpoints. They are unlimited and four-dimensional, but we go on trying to pin them down, as this moment, or that, to give ourselves, I think, a place to stand and be secure in. We want to secure the memory of the place and also to share it.

.

I knew when I asked the authors if I could write about their collection that there would be two ideas that I would have to riff on ..the idea of ‘landscape’, and the business of collaborative works. Let’s start with the idea of landscape..because that’s what it is. An idea. A concept.

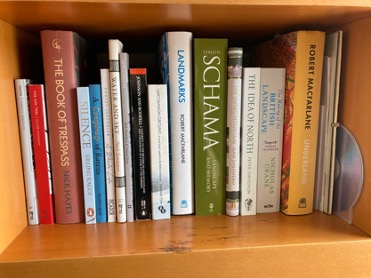

Raymond Williams’ The Country and the City is missing from the shelf, but otherwise it’s a fair cross-section of the books that have explained the the notion of landscape for me by teaching me its cultural history. The word arrived as landscipe or landscaef in England after the 5thC. It meant land shaped …by farming and clearance for instance. The word landscape, first recorded in 1598, was borrowed from a Dutch painters’ term. In other words, a piece of land specifically chosen to be looked at and visually recorded. It gets tangled up with the idea of scenery, and backdrop and setting. Think of the Breughels, Elder and Younger…their huge vistas full of human activity, or, closer to home, Lowry’s teeming industrial cotton towns. At different times the fashionable ‘landscape’ might be Sublime and awe-inspiring (Caspar David Friedrich, Turner, Anselm Adams) and at other times pretty and and managed and Picturesesque.

I’ve read and read trying to understand my own preference for particular kinds of landscape. I’m not at home in woodland or in conventionally ‘pretty’ countryside. I’m uncomfortable in flatlands where the sky’s too big, and everything is too far away. I’m happier looking down rather than up. I like to be on the tops of things. I’m immediately in tune with the first stanza of Offcumdens’ title poem, in which Emma Storr announces

I didn’t know I’d fall in love with bleak:

the swerve of dry stone walls around the hills,

the fissured scars of rock above the fields.

It may be, too, that it comes with its own language of ‘north’. The Norse ‘k’, the stone, the hills, the scars, the fields. A language and a place in tune with each other. It reminds me that I have two poet friends ,each of whom have a house which embraces a 180° view; one view ranges from the Dark Peak, via Holme Moss and the moors above Halifax and Bradford to the beginnings of the East Riding. The other one, on the horizon of the first, looks out north over Ponden Reservoir as far as Whernside. To be in either place is simultaneously to be grounded, and like flying. It’s also to be immersed in the sound of things, wind especially, and also its texture. Essentially, I’m saying that when it comes to writing about Offcumdens I’m a captive audience.

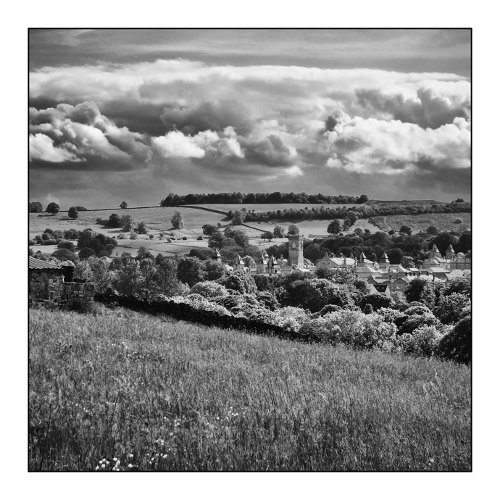

Another thing. A landscape is a much more complex thing than a photo or a painting. I believe, like Robert Macfarlane, that you only come to ‘know’ a landscape by walking in it, physically knowing the effort of hills and hard ground, or the release of level turf. Equally, walking in its weathers, wet or dry, cold, blustery, calm, humid. One of the things I like about this collection is its range, from the hard uplands of the Northern Dales, to the limestone cliffs of the East Coast, the scooped trough of Upper Wharfedale, the tucked- in small valley towns, and also curious corners of the big cities like Leeds. All of these places have been walked, explored on foot, in the way that is constantly shifting the perspective and arrangement of things in time and space. And this creates an energy, and organic sense of living places that are worked and populated.

.

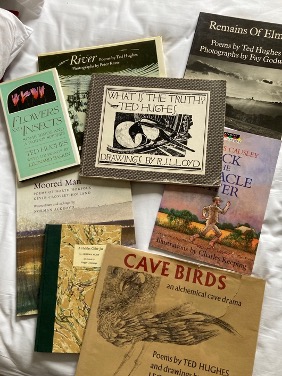

So much for landscape. The other attraction is that of a collaborative piece. I’m fascinated by the interaction of different ways of seeing, and often wonder about the process. For instance, how did Norman Ackroyd work with Kevin Crossley-Holland? Which comes first…the poem or the artwork/photo. Did Fay Godwin and Ted Hughes work independently and then see what came up? It looks fairly clear that R L Lloyd illustrated the poems that Hughes had written, as did Charles Keeping for Charles Causley. The dynamic is going to be different all the time. [Note to self: maybe I should ask Stella Wulf about her collaboration with Graham Mort. And also about her illustrating her own poems. Hmmm.]

The thing about Offcumdens is that a) it has the courage to work in the same territory as Hughes and Godwin and b) it rather wonderfully provides the reader with an appendix of detailed commentaries, in which Bob and Emma write about their involvement in particular poems. There’s one telling moment when Bob, writing about the poem Walking away, says

“Emma is called upon to be very patient while we’re out walking together. I see something in the landscape that I think will make for a good photograph, and go running off to find the right spot……I often see shapes and textures in the patterns of the clouds, imagining how they are going to look in black and white…”

Emma’s comment is that

“It can get very cold waiting for Bob to take photos…this was in March with frost on the ground and a bitter wind”

I really like the sense of the to-and-fro of the collaboration in which sometimes the image will generate the poems, and at other times the photographer will work to respond to or illustrate the poem.

As Philip Gross writes in his endorsement on the back cover: “Each double page is a conversation” . Each pair of facing pages is made of an image and its companion poem. A conversation.That’s it, exactly! Time now to eavesdrop on three of these conversations, which I hope will give you a sense of the range and richness of this lovely book. First up, let’s meet our guests.

Bob Hamilton is a Londoner who moved to Ilkley in 1988. He has a background in mathematics and spent his working life as a software developer, involving everything from computer games in the 80s to image databases in the 90s—pioneering the first systems for museums to display their photographic archives on screens—to public health systems in the 2000s. Somewhere in the middle of all that coding he took a sabbatical to write a non-fiction book called Earthdream (Green Books, 1990), a work of ecophilosophy. With his family having spread its wings, he has found the space to pick up his camera and his pen again, pursuing a number of photography and writing projects. He has won a number of open photography competitions and has had his pictures exhibited nationwide through The Photographic Angle.

Web: www.earthdreamery.co.uk and www.facebyface.org.uk

Emma Storr is also a Londoner who moved to Leeds in 1993. She has a background in medicine but is now turning her attention to poetry. She completed an MPhil in Writing at the University of South Wales in 2018. Publications include poems in The Hippocrates Prize Anthologies of 2016, 2018 and 2020, Strix Nos. 2, 3 & 4, Pennine Platform Issues 86 & 87 and Raceme No.8. Her poems have appeared in the following anthologies: These are the Hands, Fairacre Press 2020, And the Stones Fell Open: A Leeds Poetry Anthology, Leeds Church Institute 2020, When All This Is Over, Calder Valley Poetry 2020 and Bloody Amazing, Dragon-Yaffle Publications 2020. Her debut pamphlet Heart Murmur was published by Calder Valley Poetry in 2019 and has a medical theme, based on her work as a GP. And she’s also been a guest on the cobweb. Here’s the link https://johnfogginpoetry.com/2019/01/13/on-hearing-and-listening-and-an-undiscovered-gem-emma-storr/

Web: www.emmastorr.co.uk

I asked Bob and Emma for three poems. The first one is dedicated to cottongrass which the long-distance walker John Hillaby described as an ecological warning sign of of a soil beyond regeneration. It’s the flower of the gritstone moorland tops. It’s fragile and beautiful. I loved the idea of its being gathered by a distraught Ophelia

.

Bouquet

Poor Ophelia with her floral gifts.

Pansies never eased her heart or cheered.

Forget the rosemary, columbine and rue,

the daisies and the fennel’s feathered leaves.

By the river, far from sniffing dogs

I’ll pick white stars of garlic growing wild

and in the hills I’ll find the nutty scent

of gorse, the yellow tongues among its thorns.

I’ll gather cotton grass, the tufts that rise

from swamps to dip and dance in gusts of wind.

My garland will have barley and sea thrift,

stems of pink and purple Yorkshire fog.

I’ll give my lover flora from our walks

in sprinkled woods, on moors, on salt-licked cliffs.

.

The second one I asked for is a less obvious choice, but I wanted to reflect the fact that this collection takes in the variety of a much-worked and imbricated landscape. There are many images of high moors, but the soft valleys around Ilkely and Menston can sometimes be home to bleak and disturbing memories.. Menston was one of those asylums like Storthes Hall that were built in the 19thC and in recent years abandoned or turned into apartments..or student accommodation ….with the rise of so-called ‘care in the community’. My own reading of the poem, which I think is heartbreaking, is coloured by re-readings of a novel by William Horwood whose daughter was born with severe cerebral palsy. Horwood writes multilayered intra-textual stories involving invented mythologies, actual documentary histories and imagined biographies and publications. This one’s called Skallagrig. It was published by Penguin at some point.I think it’s wonderful. It appears to be out of print but you can pick up used copies starting at around £6.50

West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum

.

Is this home? I forget.

Stains on green and brown walls

are clouds above my bed.

.

I watch the ward canary fly

from its cage towards the light.

Sometimes it grips its perch,

stays within the bars.

.

Sometimes I prefer the dim

inside, the dull calm.

.

They say it might be good for us

to have fresh air, to weed and rake

the flower beds and walk

the grounds as if we’re free.

.

Marshall tried to hang himself.

The gaslight bracket broke.

Lavatory chains can’t be looped

into a noose or knot.

.

We are watched over,

overseen.

.

Did I mention the orchestra?

Music made from lunatic strings,

brass and drums, we beat

the wildest rhythms, dance

our madness in and out

with stamping feet and whirl

the staff about until they beg

to be released from jigs and reels.

.

I think that this is home.

.

A garden for nesting birds,

the greenest grass,

the smiling face of a clock.

The final choice I couldn’t resist. The Brontes had to find a place. Unsentimentally.

.

Haworth Hills

.

I dreamed last night of Haworth hills,

misty moors and damp days past,

trudging pattens on the cobbles,

Emily breathing hard and fast.

.

I saw their rooms, the tiny books

Branwell’s painting, creased and brown,

a battered trunk, a Scarborough grave,

lives of passion, all cut down.

.

I watched the father find his stick,

place his nightcap on his head,

stiffly kneel to say his prayers,

cursing God he was not dead.

.

Today the Brontës sell as soap

and broken biscuits by the pound.

Thousands come to walk the moors

worshipping the hallowed ground.

.

The air is clean, the drains are clear,

the deathly coughs are buried deep.

The Brontës have been sanitised,

their untold stories put to sleep.

.

So there we are….it’s taken some time to put this together what with a spell of Covid followed by debilitating complications. I wish my mind was clearer. But thank you, Bob Hamilton and Emma Storr for being our guests and sharing the riches of your book.

I guess everyone will want to buy a copy. I hope so, anyway. Here’s the detail

Offcumdens: Hamilton and Storr . [Fair Acre Press. 2022] £19.99

See you next week. Or the week after.