After 400+ posts on the cobweb, I’m bound to repeat myself, I suppose. But I still have to remind myself that when I started it, it was simply to share my enthusiasm for poets who I called undiscovered gems…or (un)discovered gems. It depended on whether they’d already been recognised by a publisher and had work ‘out there’.

Over time I got distracted by what seemed like the need to sound off about the business of poetry in general, and on occasions, like last week, to have a bit of a strop. Mea culpa. I’m determined to get back to basics, albeit not on a weekly basis.

So here we go, with a poet I’m very fond of; I’ve enjoyed listening to her at Poetry Business Saturday workshops, and I’m delighted to have a guest who, among other things, has been active in the campaign to save Sheffield’s street trees and was arrested for the first time at the age of 70.

Jenny has a background in Anthropology and had a career in Sociology. If I’d only read her poems, I’d have guessed at Archaeology..I think a lot of her poems are like careful excavations. Jenny has written that her aim has been:

to notice the everyday and give it due weight. And that’s what I write about mostly, my lived or remembered everyday. I want to hold or recover the moment and gently scrutinize it

I think this illuminates all her work. It chimes with MacCaig’s lines in An ordinary day

‘how ordinary

Extraordinary things are or

How extraordinary ordinary

Things are, like the nature of the mind

And the process of observing.’

Jenny writes about memories of childhood and family (and the memorials of them enshrined in documents and objects, the work of their hands). The response to this might be a world-weary doesn’t everyone? The family anecdote, the familiar, the quotidian are staples of our memories. But poems that we remember. that seem to memorise themselves as we read take us beyond that. They surprise. They illuminate our own experiences. They will involve what Clive James calls ‘the moment that draws you in’ and what Jane Draycott calls ‘the point of ignition’. Let me share some of the moments that drew me in, and then Jenny will tell you a bit about herself before I share some of the poems with minimum interruption.

I was born dwarfed by the dead and/all their impedimenta , she says. And that last unexpected, accurate word lifts the idea out of the ordinary.

She sleeps , (as we all do, without thinking about it ) under a bedroom ceiling, the other side of which is the dustbound side of everyday.

Which is how, from now on I will have to think of lofts and attics. Which may, or may not, store memories, and which she searches out:

to a high shelf..[she says]….. to a legacy of albums and attaché cases /I take my ignorance

Of a painter- Grandfather she writes about how she comes to take possession of his

sunlit room, and something up there

laid out above his wardrobe

under the pall of a dustsheet’s folds

Here, the past is probably unnerving, and tantalisingly out of reach, or possibly forbidden. These images stick. Her observation is acute, too, as in the cleaning of a fish and its stamp-hinge scales. Love that one. I like the bit of grit that jams the Dyson, a bit of grit that comes out of Deep Time; grit the oyster turns to pearl in a later poem.

I love the house of (I think) an elderly relative, up a

fern-choked clough….a nudge of pasture at her kitchen window.

So far, so Laurie Lee. But then there’s a line that stops me dead in my tracks: Cute as a grave/ here’s her garden.

There are poems about birds and animals that remind me of MacCaig (again). A mouse in the house has battery-powered whiskers; birds in the garden trees are perched like saints or green men.

I could go on. But I think you get the point. Enough. Here’s Jenny to introduce herself, and then some poems she’s shared.

“I am a poet and until recently an active academic. Then I gave up the day job to find more time for poetry. I wanted to feel, think and hear through poetic language, as well as the academic words I had written in their many thousands. Memory, loss and the objects that survive us have been longstanding research interests and they remain an important inspiration for writing poetry.

Ed. : Why poetry, why poems? I ask

Rupert Bear Annuals were a feature of my early childhood. My grown-ups only read me the text under the pictures and I now discover it’s all end-rhyme couplets. Did that set my ear? There was little spare cash after my mother divided the housekeeping into her five labeled tobacco tins in the kitchen drawer, but she bought me Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘A Child’s Garden of Verses’ one Christmas, and I adored it. I wish I could recapture what its simple language evoked for me, so skillfully written from a child’s point of view: the child in its bed; the child watching from the window; the child re-imagining its garden as a battleground. I never wrote anything myself but I did read and re-read and re-read A.S.Collins ‘Treasury of English Verse, New and Old’, given to my mother by my father ‘with my very deepest love, for Christmas 1946’, an inscription I could never marry with my parents’ apparently boring lives. I was six months old that Christmas. Did Mum find time to read it, with a new baby and no washing machine or fridge? And with ‘duty before pleasure’ as her mantra.

Me reading aloud A.S.Collins ‘Treasury in bed on long light evenings makes me smile at myself now. As a parent (and grandparent) I think it might unsettle me to hear a child intoning poems for what I remember as hours. What did I actually read? Wordsworth’s ‘Westminster Bridge’, Coleridge’s ‘Frost at Midnight’ and Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’, almost all of Keats and Tennyson, Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’, Hardy’s ‘The Darkling Thrush’ , almost all of De la Mare and then Masefield’s ‘Sea-Fever’

Ed.: which I find impressive and unnerving in equal measure

As a young parent I wrote little, but kept the faith. Two of the four poems I eventually produced in the early 1980s were included in The Raving Beauties’ No Holds Barred (The Women’s Press, 1985). That set me off, with regular Arvon courses and The Mutiny Poets group in Hull. In 2013 I received a New Poets Bursary Award from New Writing North (http://newwritingnorth.com/) and, after magazine and anthology publications, my debut collection, Going to Bed with the Moon, is now available from Oversteps Books.

I’ve written as a member of Cora Greenhill’s inspiring poetry workshop for women, ‘Living Line’; I’m also a member of Tuesday Poets, a workshopping group, and of The Poetry Room, a group that reads poetry collections as well as workshopping its own poems. I also relish The Poetry Business’s Saturday writing days and absolutely value its presence here in Sheffield. where I live with Bob, my partner, in a house sandwiched between two parks. I continue to write about loss, but also the tree- and bird-filled landscape that surrounds me. And along with my leaning towards the downbeat, I am always inspired by the quirky, surreal and laugh-out-loud hilarious nature of everyday life.

When my debut collection, Going to bed with the moon came out with Oversteps in 2019, I introduced myself at the launch as ‘a recovering academic’.

Ed.: you can find out what that involved by following this link; it’s impressive..https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/socstudies/staff/staff-profiles/hockey#tab00

I’ll still put lots of words into long complicated sentences when I write poetry. Or still assume too much on the part of the reader. But being trained as an anthropologist did sharpen my capacity to notice the everyday and give it due weight. …….. I’ve never visited Mars or Atlanta in a poem, never taken on the persona of a historical figure or inhabited a painting by Breughel. But there’s still time.”

Ed.: To which I add: oh yes there is

So. As everyone says. For no reason at all. The poems. First from Going to bed with the moon, which the editor descibed as a collection which moves from the beginning to the end of the day, and from the familiar world of home to unknown travel destinations and their imagined challenges.

There are a lot of poems about remembered tactile love in the collection, bound up very often with memories of foreign travel, a touch of glamour. I chose this one because of its compression, its absolute assuredness, because of the image of layers, an idea that quietly and unobtrusively runs through the book. I think its a stunner

Concrete and Clay

We lay there a long time, really

chilling to the draught which blew beneath the door.

We were like statues, weren’t we,

one above the other like folded rocks,

massive in our contentment.

It mattered to us then

if you remember.

Jenny says : I’ll still put lots of words into long complicated sentences when I write poetry. I’m not sure if the next poem is the kind of thing she had in mind, but what grabbed me was the way the matter -of -fact, decidedly prosaic language of the ‘memoir’ is suddenly transformed into something quite other in the second stanza. Maybe the pivot is that ‘cut throat razor’, but Grandfather’s suddenly not a comfortable old buffer. There’s something of the folk tale about growing longer than the alcove, and sonething decidedly insettling about the line

and I came intopossession of his bed

And as I said before, the last four line absolutely nail it.

Meredith Charles Watling

.

was an acknowledged East Anglian

painter, I read in the 1955 obituary

that fluttered from the unlocked leaves

of my mother’s diary. He filled our house

with the scent of linseed and St Bruno

pinched from a flat Bakelite pouch

with a screw-off inset lid; pared his nails

with a knife, stropped a cut-throat razor.

.

When I grew longer than the alcove

in my parents’ room, they moved me

downstairs by Grandad’s easel and paint

— until Addenbrookes took him one night

and I came into possession of his bed,

his sunlit room and something up there,

laid out above his wardrobe,

under the pall of a dustsheet’s folds.

.

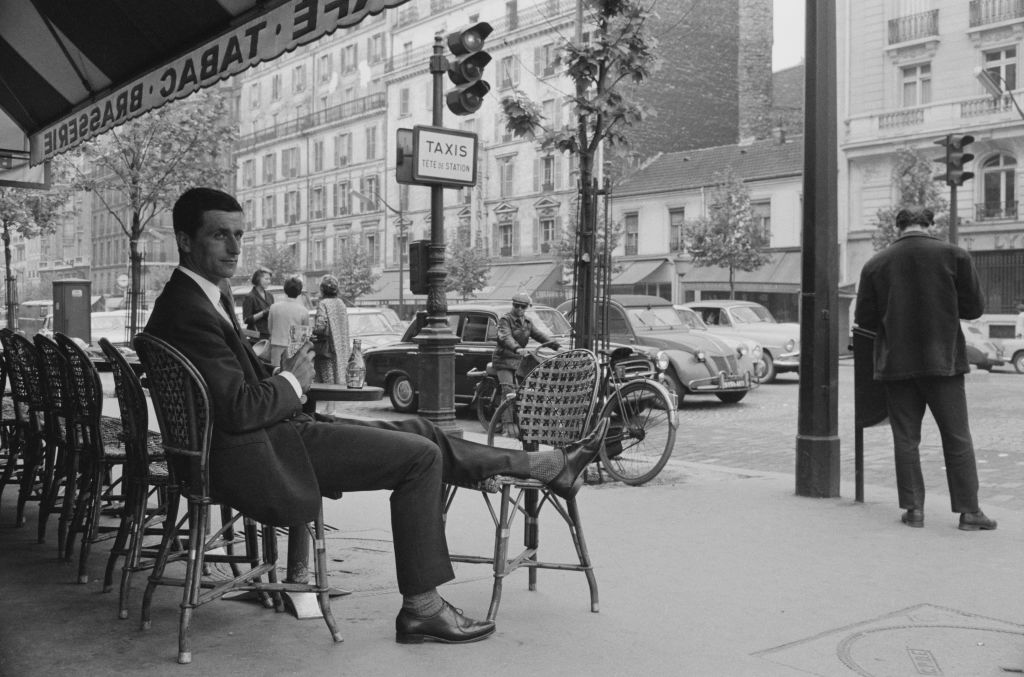

One more from the collection; this is the last poem in the book, and exactly where it needs to be

The Party’s Over

.

Oily scraps of veg, drabs of bread

and napkin shreds,

red wine, salt and cigar butts

and I’m drink-dazed for sleep,

drained with the weight

of my own unspoken words.

.

And in the small room where three flames burn

on the green fish candlestick

that I cycled seven French miles to choose for myself

at the cost of several hundred francs,

I spit on my finger and thumb

and draw down the darkness.

.

I like this for its filmic quality, the way the camera moves slowly, the way it lingers, the way it takes us through the house to the last room. I love the assuredness of the narrator, the conjuring of the darkness. I love the way the screen goes black.

And now, to finish, the bonus of two new poems, a bit edgier, a bit more swagger. And that trademark thing of the unwritten subplot…as well as another attic.

Jesus with Guinea Pigs

There’s always something to be done in our house.

But in between, my mum gets out her paints, completes

another Jesus and props his wet radiance on the easel,

.

his wounded body hanging there as I walk in from school,

fists clutching roadside grass grubbed up for Ginger

and Bobby Charlton squeaking their heads off in the shed.

,

Always that quiet conversation going on — something about

The Other Side, evidence of uncles who have crossed over.

Mum and Mr Sperring, the worry of his gifts.

.

Relic

Easter and I’m crossing the Cleveland Hills,

Losing My Religion full on through the sun roof

.

as you stow the relics of a dead husband

in your attic, filling a tall house

with withered climbing gear,

.

a grounded kayak I later help you free.

Picture us down at the quayside, posing

by the whale bones, the Abbey’s silhouette.

.

Thirty years on and you’re not

anymore, I’m losing my religion.

.

Jenny Hockey, you may be losing your religion, but you’re not losing your touch. Thank you for being a guest on the cobweb, and for sharing so many poems.

Right.I think everyone should now follow this link, and buy the book