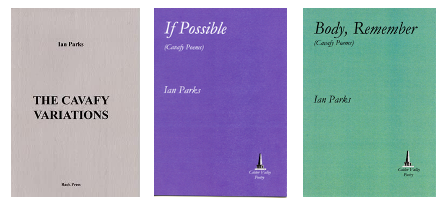

Miles to to go, and promises to keep. It’s not the first time I’ve promised to write about the work of someone I owe a debt of inspiration to. For one reason and another, it took me months to bite the bullet and write a review of Yvonne Reddick’s work on Ted Hughes as an eco-poet. And equally, to sit and write about Ian Parks’ translations of Cavafy : Body Remember [Calder Valley Press: 2019]. As headline poet, he introduced it at The Puzzle Poets Live in the Navigation Inn in Sowerby Bridge. August 2019. And I said I’d write about it. Over a year has passed. Covid has been a distraction, but no excuse. Mainly, it’s been down to a diffuse terror that I’d not do him justice. It won’t do. Because the voice of these poems is one we desperately need in in the sleep of reason we’re currently living through. Bugger it. Here goes.

If you are a follower of the cobweb, you’ll have encountered my enthusiasm for Ian Parks’ work before. If not, then you might like to fill in the background by following this link, which will give you a flavour of his voice, and also a detailed bibliography

https://johnfogginpoetry.com/2018/02/04/them-and-uz-or-just-us-and-a-polished-gem-ian-parks/

You might also have come across other things I’ve written about my feeling of temerity when it comes to approaching or evaluating someone’s translations of other poets’ work. I wrote a revirew of Peter Sirrs’ Sway, his translations of troubadour poems from 12thC Occitan. I bothered for ages about the business of translation/homage/retelling/inhabiting. As a life-long monoglot, I bothered about the problems of the business of affect and connotation. A good friend, the Spanish poet Alicia Fernandez explained for me what this might mean even to a fluently bilingual professional translator and gifted poet.

“Behind the things we write about, and the way we write about them, there is a heavily-loaded layer of meaning guiding our choices for words. I believe these choices are based on how our own life events have allowed us to delve in the many nuances clustered in those words. For example, when I describe something as green in English, my experience of the colour is not the same as if I resorted to the word verde when writing in Spanish – verde is the colour of the olive groves amongst which I grew up, and it makes my heart skip a beat with homesickness as I picture my grandfather hitting the branches with a wooden rod during harvest season; verde is also the colour Lorca used to represent death in poems such as ‘Romance Sonámbulo’, and having read his poetry since my adolescence, I cannot detach all those implications from the word.”

If I don’t live inside a language, how can I know the exact and complex resonances of a key word for the writer. Equally, how can I understand the music of it if I’m not even sure of how it should sound. And so on.

In the end, it was Peter Sirrs who offered two answers, one explicit and one that wasn’t even a conscious answer.

The first was a kind of response to something I read in a scholarly essay about translation (I can’t remember whose):

The translation-maker’s duty is to the original, yes; but his primary duty is to the new poem which, through the process of translation, “becomes” the translator’s poem and not just a transliteration of the original poet’s work. In this view, the translator is active and not passive; an originator and not a transporter; a transformer and creator and not just some drudge who, dictionary in hand, roots for and writes down linguistic equivalents.

Sirrs makes it even simpler in his Afterword to Sway:

“These are not, it should be said, scholarly translations…I played fast and loose with form and image.”…….. Translation is never fixed or finished; it answers a contemporary need to engage with and remake in the language we have available to us whatever calls out to us from the past”.

and finally in the key he gave me to approach the work:

It’s just one line in one of the poems: “oh I was the quare one”. I think this was the moment that I realised that one way to listen to these poems was to imagine an Irish voice; that dialect and accent were probably the key to imagining these 900 year old voices, written before the idea of French (and Standard English and R.P.) existed

I think it turned out to be as simple as that. Just listen. Listen properly. Which is what I set out to do when it came to Ian Parks’ Body Remember , the third of the trio of his tributes to, and celebrations of, Cavafy. Because, at the end of all, I firmly believe that what matters is the authenticity of the voice. And, because the loss of lives and love in time is something I think Ian Parks has particularly tuned into, I also hang on to this observation by Daniel Mendelsohn,

“The common approach to interpreting Cavafy for many, many years now is that he has two subjects: history, the Greek past from classical times to Byzantium, and then as if it were an entirely different subject, desire….

And I don’t see it that way………. I make a case for thinking about Cavafy as a poet who was only interested really in one subject, which is time and the passage of time, and how it affects how you see the past, whether that past is a Byzantine emperor’s failed attempts to restore the empire or one’s own love affair with a beautiful boy in Alexandria in 1892. It doesn’t matter to Cavafy. What he’s interested in is a relation to what has already happened. “

When I asked Ian about his long love affair with Cavafy, and about the business of translating from early 20th Greek, he wrote me this:

“I first came across Cavafy through W H Auden’s brilliant essay on him in Forewords and Afterwards. Auden was keen to point out that while Cavafy possessed ‘a unique tone of voice’ his poetry also ‘survived translation’.

I thought that was a fascinating concept and set about trying to prove to myself whether it was true. I’d be in my twenties at the time and I found, by and large that it was – in that the existing translations (particularly those by Keeley and Sherrard) conveyed something of the essence of this poets enigmatic and philosophical work. However, I became increasingly aware of how these translations were literal – that they provided a word for word, line by line, and stanza by stanza rendition of Cavafy’s poems into English.

While that provided the reader with a clear idea of the content of the poems it did little (in my mind) to convey either the musicality of this poet’s work, his undoubted lyric gift, or the subtlety of his poetic thought. And so it was that I set about to teach myself modern Greek in order to put myself in a position where i could read these remarkable poems in the original language. It took me ten years to reach a level of basic proficiency – just enough to understand the drift of the poem, much as a dog might catch the drift of human conversation through level, intonation, and tone.

My method is to transcribe a version from the original, line by line, and then to treat it in much the same way as I’d treat a first draft of my own and take it through a process by which clarity gradually becomes apparent. This way i can visualise the whole poem from above rather than allowing myself to get entangled in the detail. When in doubt I’ll compare my results with other translations in order to see what nuances emerge – but i very rarely adhere to them. My intention is always to be true to the spirit and integrity of the poem and to convey something of the atmosphere and flavour of the originals. I wanted to refract rather than reproduce, to refine rather than to define. :”

Don’t you love that line: much as a dog might catch the drift of human conversation through level, intonation, and tone.

And this after ten years of patiently teaching yourself Greek. There’s a labour of love. Love, as it happens, turns out to be another key idea in understanding what Ian does with his translations. A love which he combines with the patient task of literal translation, and the idiom, the rhythm of his own, familiar idiomatic language.

To see how this works it’s useful to have a look at other peoople’s versions of the title poem of the pamphlet: Body Remember. I’ve not found a way of setting poems side by side for WordPress, so it may feel a bit laborious. Bear with me.

One.

Body, remember not only how much you were loved,

not only the beds you lay on,

but also those desires that glowed openly

in eyes that looked at you,

trembled for you in the voices—

only some chance obstacle frustrated them.

Now that it’s all finally in the past,

it seems almost as if you gave yourself

to those desires too—how they glowed,

remember, in eyes that looked at you,

remember, body, how they trembled for you in those voices.

[Reprinted from C. P. CAVAFY: Collected Poems Revised Edition,

translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard,…probably the touchstone translation]

Two

Body, remember not only how much you were loved,

not only the beds on which you lay,

but also those desires for you

that glowed plainly in the eyes,

and trembled in the voice—and some

chance obstacle made futile.

Now that all of them belong to the past,

it almost seems as if you had yielded

to those desires—how they glowed,

remember, in the eyes gazing at you;

how they trembled in the voice, for you, remember, body.

[Trans. Aliki Barnstone]

Three

Body, remember not just how much you were loved,

not simply those beds on which you have lain,

but also the desire for you that shone

plainly in the eyes that gazed at you,

and quavered in the voice for you, though

by some chance obstacle was finally forestalled.

Now that everything is finally in the past,

it seems as though you did yield to those desires –

how they shone, remember, in the eyes that gazed at you,

how they quivered in the voice for you – body, remember

Trans. Stratis Haviaris

You read them aloud, and you can start to ask what difference is made by the choices of ‘lay on’/ ‘on which you lay’/’on which you have lain’ to the tone and feel of the poem..as well as its rhythm, its music. Whether a slightly archaic syntax is the right thing. And so on. What about ‘tremble’ versus ‘quavered’?

And what about

only some chance obstacle frustrated them.

as opposed to

some chance obstacle made futile.

or

by some chance obstacle was finally forestalled.

As you work through them, line by line, considering the choices, I think that, like me, you’ll become conscious of bum notes, little snags.

Now try a different tack. What’s Cavafy writing about here, in his later years? What’s he asking for…not for what can’t be brought back, but what is in danger of being physically forgotten. We take for granted that the body has the wonderful facility for not being able to remember pain. The circumstances yes, but the actual pain, not at all. But what if the body forgets sensual, tactile, auditory pleasure, the loveliness of it all.

Now, here’s Ian Parks’ version.

Body Remember

Body, remember how much love you drew –

not just the beds, the hot illicit rooms

but how that love so fiercely burned

deep in the eyes of those that gazed on you:

how voices trembled even though

some random moment always intervened

to stop the dream from coming true.

Now everything is contained in the past

it feels as if, in fact, you gave in to

all those desires that fiercely burned;

remember, through the eyes of those that gazed on you,

or the voices trembling. Body, remember.

I love the tenderness of this, its authenticity of voice. The way you forget that this is Poetry in the way that the other three translations are constantly reminding you of, if only because they don’t quite get it right. A reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement put it better.

Parks captures the measured graceful voice and quiet humour on which so much of Cavafy’s poetry depends in a way that makes us feel we are reading it properly for the first time, This, you feel, is exactly what they would sound like if they had been written in English.

I’m struggling to choose another from the pamphlet, because I want to choose them all. I could choose any of the ones that celebrate craftsmen..jewellers, for instance…and painters and poets who quietly observe themselves making art. But I think I’ll settle for this, about Caesar’s son, who is called to an imagined life as the light fades in the poet’s room.

Kaisarion

My intention was to check the facts,

to pass a quiet hour or two

among the names and places of the past.

The volume that I chose contained

a history of the Ptolemies.

The praise becomes monotononous:

the men are just, magnificent and bold,

the women upright, beautiful.

.

Just as I was about to close the book

and place it on the shelf

I came across the briefest mention of

Kaisarion – Little Caesar, Caesar’s son.

I was drawn to it inexplicably.

.

You stood there full of praise and charm.

Because the record is so sparse

I filled the sketch out in my mind,

made you sensitive and shy –

a dreaming far-off face

despite the name they gave you, King of Kings.

.

So vivid did I conjure you

that as the lamplight dimmed

you came into my darkened room. came close and stood in front of me

weraing the expression that you wore

in fallen Alexandria,

imploring them to pity you –

Octavian’s henchmen, those murderers

who said One Caesar is enough

I suppose at this point I could share more poems from the pamphlet. But I won’t. Just go and buy it*, discover its range and its many voices as it travels between the worlds of classical/historical Greece and of the early 20th C.

- here’s your link to the shop: https://caldervalleypoetry.com/book-shop/

Instead, Ian has sent two more , as yet unpublished, versions of Cavafy poems. There’s a bonus.

The Horses of Achilles

after Cavafy

The horses of Achilles wept

when they saw brave Patroklos dead.

Immortal, they were stricken by the sight –

the unforgiving handiwork of death.

They drummed the ground, shook out their manes

and reared their wild, magnificent heads.

They mourned Patroklos, mangled, killed,

his precious life force fled

into the great void of nothingness.

.

Zeus saw them weeping and he said

I now regret the wedding gift I gave

to Peleus on that day. Better had there been no gift

than for you to suffer in the world of men.

You’ll never sicken, age, or die

and yet you weep like this to see

how men have brought about such misery.

It was not merely for Patroklos

but for the universal certitude of death

that those noble horses’ tears were shed.

Very Seldom

after Cavafy

Stooped with age, the poet makes his way

along the narrow street that takes him home.

Affliced by time and the excesses of his life

he hides his crippled body from the light,

his mind reliving how things used to be.

.

And now his poems are all the rage:

their lustre burns whenever they are read.

His sensual verses come alive

in the eyes and lips of these young men.

.

It’s possible, of course that one of ‘these young men’ is Ian Parks.. Thanks for being my guest, Ian, and sharing this labour of love.

Thank you, John, for this illuminating post. You have a way of talking to the right people and extracting exactly the right quotations, bringing your insights to life for the reader. I think it’s maybe because you wrestle with the subject that gets you to the heart of it. It’s the right size of nugget for me, not too much general theory, not too much exemplification or explication, but a choice focus on the practice and craft of translating poetry, which has always been quite baffling to me.

Regina x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regina! Thank you for this. I anguished long and hard over the ‘review’ because I know less than nothing about the the arcana of translation. You have the gift of more than one language (something you share with Alicia Fernandez, my other bilingual writer-chum). Anyway, you made the sun shine on a dreich afternoon. Don’t you love that word ‘dreich’? Damp and dire and drenched. xx

LikeLike