Growing deaf is hard to explain. Harder than explaining failing eyesight, which you can demonstrate, with a picture. I’m reminded, too, that some eye conditions might account for the spectacular success of some painters. There’s a fascinating book by the ophthalmologist Patrick Trevor-Roper: The world through blunted sight ; first published in 1970, it presents a fascinating study of the work of painters, sculptors, poets and prose writers throughout history. Was Impressionism born of a generation of short-sighted artists? Was Constable’s fondness for autumnal tints due to colour blindness? Did Modigliani actually see his nudes as unnaturally elongated through distorted sight? Leonardo, Rembrandt and Titian all suffered from increasing long-sightedness in old age – is this the cause of the loss of detail in their later paintings?

And so on. I get that, but I’ve never understood how Beethoven coped with being deaf.

Having lost about 50% of my hearing, even with hearing aids, there’s a lot of music I can’t listen to because I’ve lost all the top end (which makes the sublime Everley Brothers sound as though they’re singing flat), and being in a pub for a reading can produce a sound effect in which all the individual sounds claim equal value and lose their relative depths and distances…the sound equivalent, I suppose, of an out of focus image, which can be quite pretty until the image you’re looking at is print.

Where’s this all going? In December, I was on a writing weekend, with readings from extremely gifted poets in the evenings. It may have had something to do with the room, which was very large, but I found I could hear them only in the way I can see that grey image that I think may be about multiple choices. I heard them, but couldn’t listen to them, because listening implies you’re making sense of what you hear.

Now, where was I? There’s been a three hour interval while I loaded a futon mattress into the car, got the firewood in and went to a cold rugby match. All of which I enjoyed. A chap can lose track. Ah, yes..hearing (listening later, that was it).I’ve been to several readings since the start of December, and what I especially liked about them was that I could hear the poems. It was nothing to do with the mic being set right. It was all about the the readers and their delivery, which was so clean and clear I could do without hearing aids. One reader was Julia Deakin, who is always accurate, distinct. One was Tom Weir (twice) who read quietly, but always with that concern for the heft and texture of the words, who, like Julia, tastes the consonants that matter, and also, like her, reads with a rhythm that falls on the key words, so sound never displaces meaning, never over-rides the syntax and the sense, and lets the words have their surrounding silent space, which is the aural equivalent of white space on the page. And one poet was today’s guest, Emma Storr, who I’d never heard reading before and who was a revelation. We all know poets, some of them famous, who simply can’t read like that. I wish they’d make the effort. It’s not about theatricality, or volume or elocution. It’s about diction and a concentration on the meaning of the words they say. Thank you Tom and Julia for letting me hear the poems, and thanks to both of them for respectively guesting at the last session of The Puzzle Poets Live (at The Shepherds Rest) and at the first of a new venue which we hope will now be our permanent home..The Navigation in Sowerby Bridge. And so to our guest.

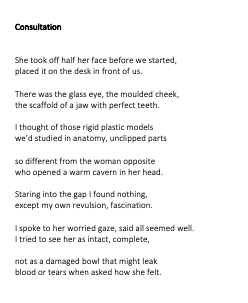

Emma is a member of Leeds Writers Circle and has a background in medicine and teaching but is now turning her attention to poetry. She recently completed an MPhil in Writing from the University of South Wales. Her poems have been published in The Hippocrates Prize Anthologies of 2016 and 2018 and Strix Nos. 2, 3 & 4. Emma is currently putting together a collection that celebrates the extraordinary workings of the body. It will be published before very long by the estimable Calder Valley Poetry. Look out for it. She enjoys the challenge of using her scientific knowledge and medical experience in lyrical ways to create different voices and styles.

I remember saying at her reading that all doctors would benefit from a thorough immersion in poetry, in writing it, in developing the empathy, the imaginative reach for the other that it demands. I guess that’s because I’ve occasionally encountered the opposite…like the surgeon who breezed past my hospital bed one Monday morning, saying airily, en passant, good, good, everything normal. I was guilty of losing my rag. ‘Normal! Normal? It’s not ****ing normal’. He was torn between being haughtily cross and being taken aback. The junior doctors all looked shocked/worried. I told him that it might be a normal day for him, and that I respected his professional skill, but I’d be grateful if he respected mine. My specialism was language and communication, I told him, and when you have been sliced open from groin to sternum and then put back together with 30 staples, and you haven’t had any solid food for over a week, and you are in some pain ‘normal’ didn’t do it. And so on. To be fair, we got on pretty well subsequently, but it was partly why my heart sang when Emma read this first poem.

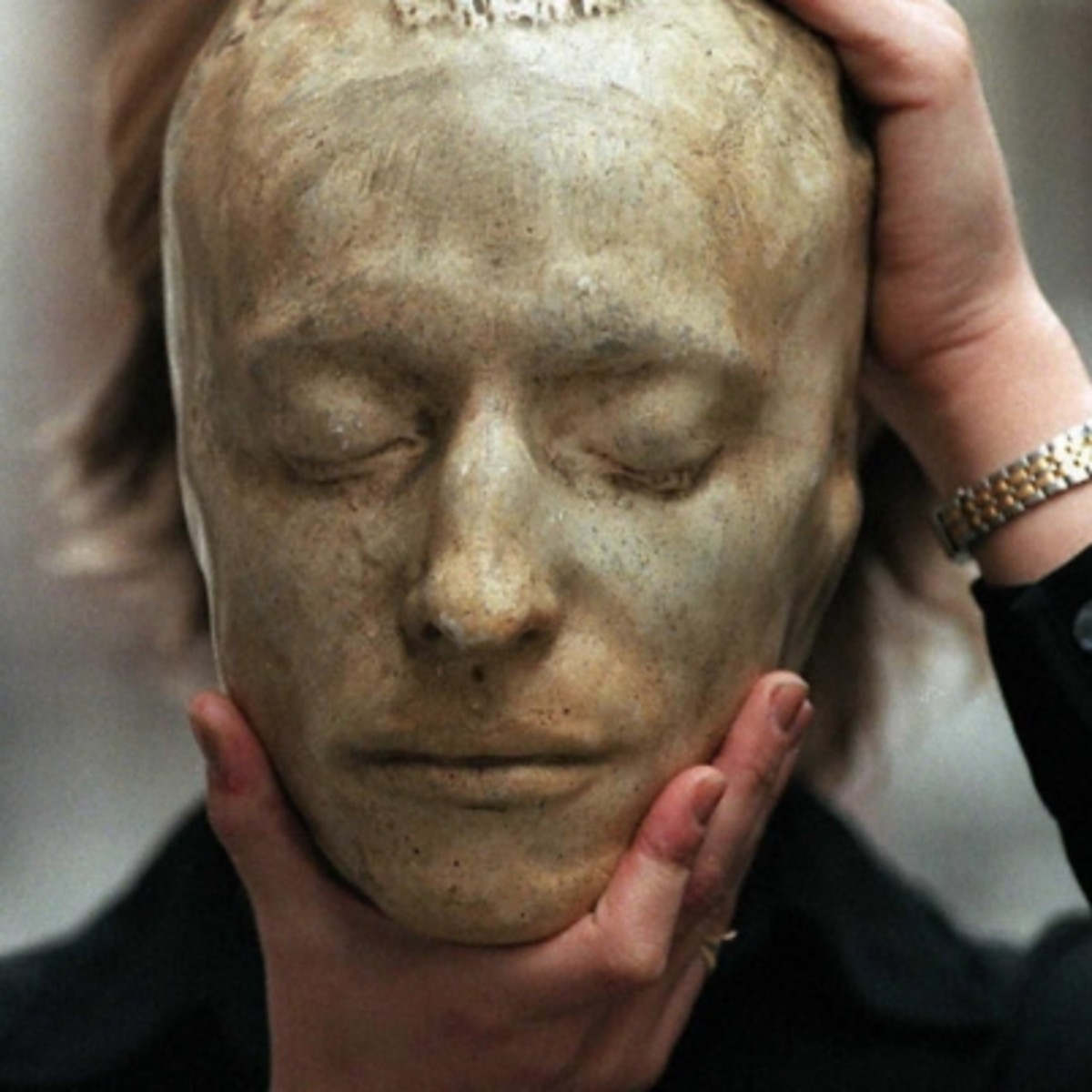

What struck me was the calm objectivity of the voice, the way the poet/doctor dissected her own response to the shock that the first line delivers in its matter-of-fact way. There’s something particularly unnerving about the phrase ‘half her face’. It’s a phantom of the opera moment, except that it ‘opened a warm cavern in her head’. That ‘warm’ is beautifully juxtaposed with the the only previous reference point of

‘those rigid plastic models / we’d studied in anatomy

and having no resource but to pretend this is ‘normal’, to say ‘all seemed well’, to ask ‘how do you feel?’. It’s a poem about the falling short of language and of emotional resource. I thought it was special. It illustrates the difference between hearing and listening, and the way the latter means you not only have to imagine who you’re talking to but to imagine who you are at the same time. I love its emotional honesty and the way it’s contained in those calm-seeming couplets. People aren’t customers or clients. They aren’t diagrams. No wonder her poems have appeared in the Hippocrates Prize anthologies.

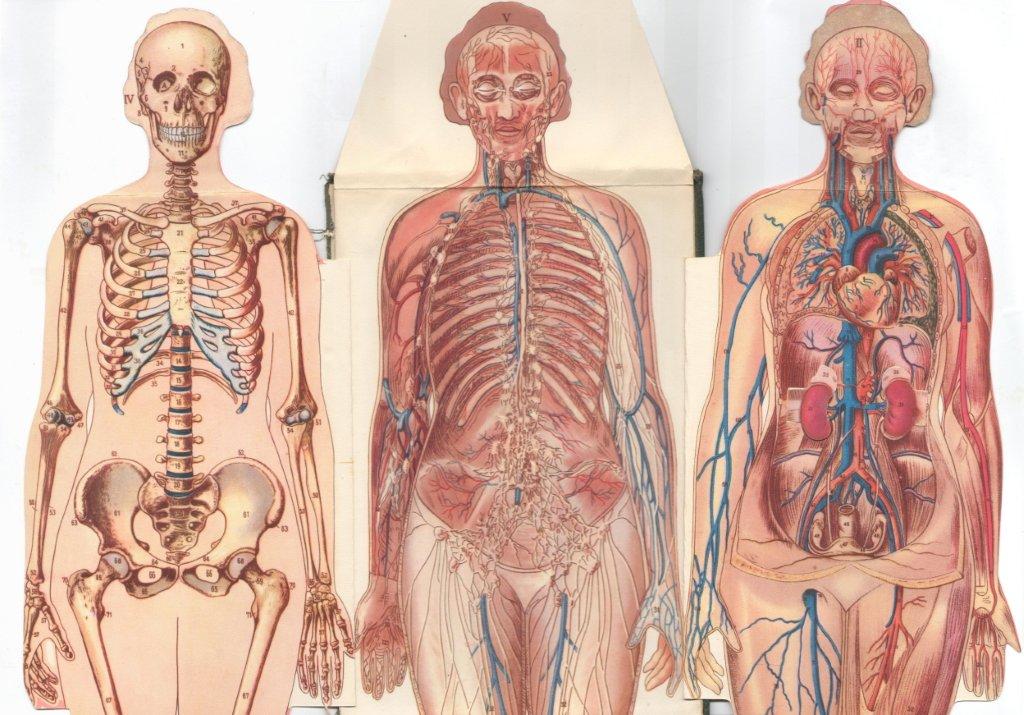

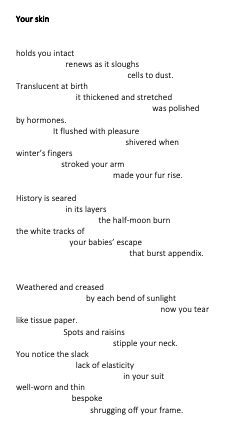

Which brings us neatly to the next two poems. (I should say that I’ve been driven nuts by WordPress’ way with lineation, and have, in desperation, overcome it by taking screenshots of the word documents. It keeps the shape and loses the clarity. We’ll get there in the end. bear with me. It was unavoidable with these two that rely totally on the way the words sit on the page.)

I’m not normally a fan of poems that play about with shape, but sometimes it’s exactly the right thing to do, as in this loving engagement with someone known who is being changed by (I take it) dementia. I like the fracture of ‘fractions’. the lengthening of ‘long division’ , the unnerving reversal of east and west, that loss of spatial compass, and the heartbreak of home hiding round corners.. I like the next poem, too

I like the visual trick that gives the text the shape of a helix, and how that tells me the rightness of the business of cell division and destruction. I like the way it steps down the page, and I like the way it made me look at and see the back of my hand (which we’re supposed to know absolutely better than anything) in a different light.

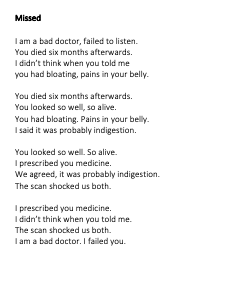

Just one more poem, that might usefully be handed out to every new doctor in training. One of my grandsons is just coming to the end of his seven years’ hard of exams and hospital placements..I think I’ll send it to him and see what he thinks.

It’s one of those poems when I want to say to the poet: don’t be so hard on yourself. It’s all very well to point fingers and say Physician, heal thyself..But if you make a mistake, how do you live with it and yourself. This poem catches, in its looping repetitions, that failure to get a sense of shame or guiltiness out of your mind, how it circles and repeats I didn’t think when I told you.

In its plainness it refuses to make excuses. It seems so baldly simple, because that’s what the truth is. So there we are. Thank you Emma Storr for the honesty and accuracy of these poems you’ve shared that tell us all we need to listen better. I’m looking forward to the collection. Please come again.

As a fellow hard-of-hearing (and which is slowly declining) person I hope your cogent expression of how some poets make a big difference to how much we can hear, get more exposure in open mics, poetry classes/workshops and performance circles. Anywhere where poets read. It’d be of benefit to listeners whose hearing is a lot better too.

“all the individual sounds claim equal value and lose their relative depths and distances”: such a good description, so much more than medical descriptions of hearing loss.

I look forward to reading and hearing more of Emma Storr’s poems too ☺. Moira

LikeLike

Thank you for this, MoiraG. Really appreciate it. Yes. Maybe we should start a campaignxxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

On a bad day teaching teenagers I used to comfort myself by remembering that at least I wasn’t working in a job where I might kill someone with my incompetence I don’t know how doctors manage, while staying human. These poems are terrific!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How did I miss your response, Grainne….yes. That’s it. That’s it xxx

LikeLike