Here we are with the first guest poet of 2019, and I’m hunting for a hook. Which turns out to be the business of the hopefulness at the start of any new year. I suppose for a lot of us who write poetry it’s the firm intention to write better this year, to send out all those poems we’ve been sitting on and humming and hawing about, and, if you’re like me, checking out the plethora of competitions that seem to come swarming around now. You might be lighting a candle for the ones you sent in for the National (which is the poetry equivalent of the Lottery double roll-over; spare a thought for Kim Moore lying on her sofa…she notes in her latest blog post that she has 9,500 poems to read through before sending in her choices for the long-list). Or you may, like me, be checking out Poets and Players or the Kent and Sussex, or Prole or York Mix……the list stretches out like Macbeth’s line of taunting kings. As regular readers know, I’m a sucker for competitions. I like the tingle. And I’ve been lucky, but it’s worth recording one illusion I was under at one time. I thought if I won a big competition, the world of poetry would beat a path to my door. It doesn’t. Basically, if you want to make a mark (which significantly, I haven’t) you have to keep on writing and working and submitting and begging for readings, and networking like crazy. The company you keep is important, but no-one owes you a living. You get the days of euphoria, and then it’s back to earth.

On the other hand, if I’d never entered and won a competition I’d never have met today’s guest who was a joint winner in 2016 of the Poetry Business Pamphlet Competition. And if I hadn’t, my life would have been the poorer. And after the most contrived hook/intro in the history of the cobweb, let’s welcome Stephanie Conn.

Stephanie launched her debut collection, ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ with Doire Press in March 2016 and, having been selected by Billy Collins as one of the winners of the Poetry Business Pamphlet Competition, three months later she launched her pamphlet, ‘Copeland’s Daughter’.

Between 2010 and 2013, she completed a part-time MA in Creative Writing under the tuition of Ciaran Carson, Medbh McGuckian, Leontia Flynn and Sinead Morrissey.

During this period, her poems were being published more regularly and in 2012, she was shortlisted for the Patrick Kavanagh Award and highly commended in the Doire Press Poetry Chapbook and Mslexia Poetry Pamphlet competitions. The following year she was selected for Poetry Ireland’s Introductions Series.

Diagnosed with Fibromyalgia, she says she felt stripped of her identity. There were so many things she could no longer do but she could still write and now had the chance to commit fully to it.

She began to arrange a full manuscript, submitted ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ to Doire Press and was thrilled when they accepted the collection. In 2015, as well as being highly commended in the Gregory O’Donoghue Poetry Competition and coming third in the Dromineer Poetry Competition, she won the Yeovil Poetry Prize, the Funeral Services NI Poetry Prize and the inaugural Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing.

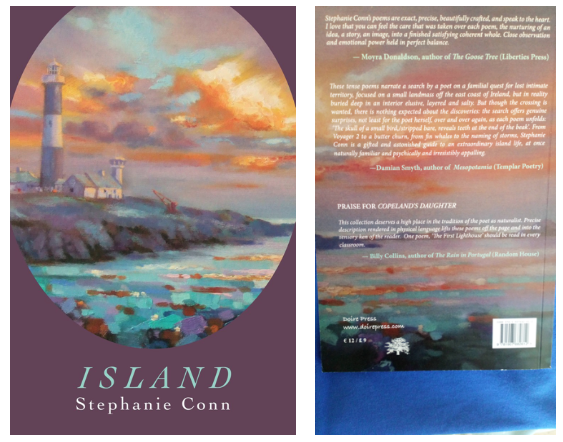

By the time Doire Press had decided to publish ‘The Woman on the Other Side’, she was already busy with new work. She received an Artists Career Enhancement Award from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland to research and begin writing her second collection, Copelands Daughter inspired by her ancestors who lived on a small island in the Irish Sea. It was a selection of these new poems that became a joint winner of the Poetry Business Pamphlet competition, after which she was giving readings and facilitating workshops, and then heading to the other side of the world for the Tasmania Poetry Festival .

There’s a c.v. to make you sit up! As I’ve said,I met Stephanie for the first time in Grasmere at the Wordsworth Trust… the prize-giving ceremony for the Poetry Business Pamphlet competition winners. She read from her pamphlet Copeland’s daughter, and blew me away. The Copelands are a small group of islands of the coast of Northern Ireland, and the poems tell tell the story of her ancestors who lived and farmed and fished there, until they were forced to leave, like so many who have struggled on poor land and in hard weathers, like the ones forced from Mingulay, from the Blasketts, the Shiants, St Kilda. So many. These poems ticked so many boxes for me. And she read with a passion, and a clarity.

I was sold from the very first poem:

The first lighthouse…Cross Island 1714.

A lighthouse in ‘these twenty acres’ that ‘never did attract the sun’

‘three storeys of island-quarried stone, picked

and carried on the convicts’ backs.

They built the wall two metres thick’

Billy Collins wrote of this poem: “The First Lighthouse” should be read in every classroom. I know what he means. It has the same kind of heft that I love in Christy Ducker’s work…coincidentally, in Skipper, the core of which is a sequence about poems about small islands , The Farnes, and the story of their lighthouse, and of Grace Darling.

Of Stephanie’s writing Collins says :

Precise description rendered in physical language lifts these poems off the page and into the sensory ken of the reader.

This, the first poem of Copelands Daughter, shows you just what he meant

Winter

We are cut off from the mainland again;

a pile of unopened letters sits in Donaghadee;

there is flour and salt and treacle in the grocer’s,

bags of coal and paraffin to fill the empty tins,

but the boat keeps close to the harbour wall.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

Still, the bread is baked and the butter churned,

the blocken cured and the rabbits trapped,

mussels are plucked from the island pools

and pickled in jars on larder shelves.

The firewood and driftwood is stacked.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

Inside the lamps are lit and curtains pulled,

while out at sea, the wind and waves confront

each other in torrents of eddies and pools

and the gulls circling above the spume

could be vultures in the thick sea-mist.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

But we know what the darkness brings;

it drags us from sleep into nightmare, lost in fog

we’ll be struck by ship after floundering ship;

forced into the driving rain, where muffled voices call

from their wreck. We’ll run to the shore to save all we can.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

In a place such as this, we are used to the ghosts,

but not to their dying; never to the bodies of young men

washed up on the shore, with their puffed up faces

and gaping sockets where the eyes should be; or the tiny crab

emerging from a silenced mouth to scurry, ever sideways.

What I really like about this is the side-by-side-ness of the routine management of household comforts, the self-sufficiencies when the boat can’t come from the mainland, the security of a storm bound house….and the way the ghosts of the drowned will find their way in, one way or another. For me, the poem turns on one plain observation that make me re-evaluate everything I’ve just read.

In a place such as this, we are used to the ghosts,

but not to their dying

Well, that was in July 2016; now it’s time for her to bring us up to date. Here she is:

“Once I returned home from Tasmania it was back to the work of writing. The research and writing on the Copeland Island built and it soon became obvious that a full collection would need to follow the pamphlet – there was more to say!

When you’re busy writing away and developing new work in isolation it is wonderful to get a little boost along the way. It helps keep you buoyant. So, it was wonderful to learn that my first collection ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ had made the shortlist of three for the Best First Collection in Ireland’s Shine/Strong Award 2016.

‘Island’ builds on and includes some of the poems from Copeland’s Daughter but moves beyond the tiny island of my ancestor’s to Ireland’s coasts – north and south. It was published by Doire Press in March 2018 and launched in Belfast in April.

In the lead up to the launch, I was busy with promotional work and interviews, and afterwards hit the road with fellow Doire-Press author, Rosemary Jenkinson, for a cross-border reading tour ‘Island Secrets, Urban Lies’ which was great fun. Most recently, we made the journey to Clare Island off the West Coast of Ireland as part of the Westport Literary Festival.

There are lots of photos of our travels on the ‘Events’ section of my website.

So much of a writer’s life is spent hidden away that it is always a delight to work with other poets and have the opportunity to contribute to anthologies and get involved in collaborations such as the Beautiful Dragons Collaboration, Metamorphic: 21st Century Poets Respond to Ovid and most recently, the Aldeburgh Collaborative, alongside other ‘Coast to Coast’ writers.

I continue to send work out to poetry journals and this year I’ve had new poems published in Poetry Ireland Review, The North, Iota, Southword, The Open Ear, Banshee, Bangor Literary Journal, Honest Ulsterman, Ofi Press, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Tangerine, Coast to Coast, Stony Thursday Book, Interpreters House and The Pickled Body.

In September, I started a full-time PhD by practice in Creative Writing at the University of Ulster. I’m working on a new poetry collection inspired by my own experiences of living with an invisible, chronic illness, as well as looking at the experiences and work of other creatives and public figures. This creative works sits alongside a critical examination of contemporary poetry of illness. That will keep me busy for the next three years, at least!

I love that….knowing where you are and where you’re heading. I’ll keep that like a small lamp to light my way into 2019. Right. Time for the poems.

The first I chose for its link to the Copelands, to islands, to hard living. I think, too, because it echoes another poem I love…Wet harvests by Roy Cockcroft. You can check it out via this link: https://johnfogginpoetry.com/2015/01/11/an-apology-to-the-east-coast-and-an-un-discovered-gem-roy-cockcroft/

And also, of course, because it illustrates what Billy Collins said about her poetry: Precise description rendered in physical language lifts these poems off the page and into the sensory ken of the reader.

Biding Time

She sits by the split cottage door knitting

a navy sweater on five thin needles –

seamless, to resist salt water, biting

winds, the neck tight enough to make ears bleed,

no swell wild enough to strip it from skin.

She knows the pattern by heart, each bobble

stitch is a prayer, each basket weave a hymn

to the deep. She ignores the new grumble

from her swollen belly, thinks of the dropped

stitch above the waist, a small gap in wool

to identify the man she loved – loves.

His worn boat has not been seen for days, caught,

perhaps, on some other island’s rocks. Still

time to return before the next storm hits.

You have to remember that a fisherman’s jumper needed a code knitted into the pattern; a fisherman gone over the side in a big sea or a sudden swing of a sail might not be recovered for days, carried miles by currents and tides, preyed on by fish and crabs. That jumper would identify the body, say where he came from. So every stitch becomes a naming and a prayer. What I like especially about this poem, apart from its empathy, its imaginative engagement, is the textures, and especially, the craft of the line endings. Exact and sure-footed. Lovely

I chose the next poem because it puzzles me and bothers me, because I can’t quite work out who’s talking to me. It’s magical; it asks for a sort of leap of faith. (it also asks for something WordPress is steadfastly refusing to do, which is to recognise stanza breaks. You’ll have to visualise them in this poem of five 4-line stanzas. My apologies)

The Saline Scent of Home

They said it was here; buried before my birth.

I had no reason to doubt them. Besides, I loved belief.

That, and myth. I could almost see it through their lens,

their open window, doorway frames, the rusted locks

but this door never did lead to the beach, not once,

and the marram grass I feel scratch at my soles

never did take root. I am both fish and toad, and neither,

turquoise and aquamarine, gills flapping, mouth closed.

I must hold my breath long enough to descend

to that air-pocket place of half-dream, and blink twice,

must look myself in the eye for the second time,

note the tint of iris, grown strange, the pupil’s pulse.

My eyes are clear, like the sea, and blue is an illusion.

The mirror’s frame is tarnished gold, layers of nacre

glint in curved drops, collapse distance. The folds

of my dress gather at my feet as liquid charcoal.

I hear an underwater echo of wood on water,

the flat slap of paddle and the time rushing in,

knowing I have not captured the moment on film,

knowing there is no time lapse of woman becoming shell.

The puzzle starts in the first line. They said it was here What is it, this it? It does a lot of work, that small pronoun. And who are they who I had no reason to doubt? Everything in this poem is dubious, the door never did lead to the beach, things are almost seen at best. Everything is fluid, everything shape shifts, the mirror distorts. It’s a dreamworld of illusion, with the strange clarity and reality of dreams. That last line is a shock, because despite the layers of nacre that shell is unexpected and unexplained. The whole poem is a moment that draws you in and keeps you there. Wherever ‘in’ might be.

One more poem to end with. Another abandoned place but more obviously rooted in a physical place I imagine I could visit, though without this poem I would not know its meaning or its histories. The voice of it reminds me of the poems I tried to write about Clearance villages on Skye, the way I wanted them to be something they may not have been. I longed, like the poet, to feel gothic. (by the way, there are no stanza breaks to imagine)

Killynether

May flowers are still in bloom by the hazel wood.

You stay to breathe in their bruised sweetness;

I walk away to all that remains of the walled

garden, rest my back against quarried stone.

All this belongs to us now. The grand house

is gone, its slender turrets forgotten –

nothing could be done. I’d love to see

its empty rooms, stripped floorboards,

an open door, but there is only fern and moss,

a rectangle of cut grass. I long to feel gothic.

Scrabo Hill rises behind me. We have strolled

the tree-sheltered track, looked back over

the patchwork slide of farmed land, kissed

at the summit. You once turned a leaf

to reveal three types of caterpillar: Grayling,

Barred Umber, Nut-tree Tussock. I wondered

if we’d see them morph into butterflies.

Today there are none. We are too far

from bark and the magic’s wearing thin.

I never wished for wings, prefer the certainty

of black dolerite, sandstone, agglomerate.

This is the only thing I cannot bear to lose.

I steady myself. Prepare to break it.

So there we are. What a great way to start 2019. Thank you Stephanie Conn. May the next three years be as productive as the last.

Aaah. .. to write poetry like that, there’s an ambition to sustain me 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

And all of us, Moira!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, John, for your careful and generous readings of the poems, and for having me back on the Cobweb, Steph x

LikeLike

You keep writing like that, I’ll keep inviting you xxx

LikeLike

Fantastic! Great to see more readers finding Stephanie Conn.

LikeLike

She’s the real deal. As are you xxxx

LikeLike