Maybe this is where it all started, the business of islands and their stories, and, eventually, by circuitous routes to the revisionist histories of writers like E.P.Thompson, Hobbsbaum, John Prebble; books like The long march of everyman; Charles Parker’s Radio ballads, and poets like Tony Harrison, and then all the way back to broadsheet ballads and the skewed histories of folksong.

But it started here, at the age of 8, when I saved and saved the prince’s ransom of 8s6d, and bought my copy of H E Marshall’s history of England (and subsequently, Scotland’s Story). The book ends with The Great War of which Marshall writes :I shall not write much at all. And doesn’t. The Victorian Age is occupied by the Crimean War, the sieges of Delhi and Lucknow, Lord Franklin, the Boer war, the settlement of Australia and new Zealand. Of the Industrial Revolution that created the streets I grew up in there is not a whisper.

This worried me not at all, because I lost interest round about the tale of Flora Macdonald and George the First…when kings stopped looking and behaving like this.

or like this

Our island’s story was the story of kings who were glamorous and bellicose, who burned cakes, and who made fields of cloths of gold and beat the Spanish and the French and went to their deaths on the scaffold with becoming dignity and gravitas. Above all, they were colourful and dramatic, and you could spend hours copying the colour plates that were the real joy of Marshall’s book. Who’d want to copy a picture of a man in a suit? For all that, the idea that islands and stories were indissolubly wedded was formed here, and reinforced forever by Robinson Crusoe, and The Swiss family Robinson and Treasure island.

Keen-eyed followers of the cobweb will have spotted straight away that this is the third post in a row (indeed, in 9 days) ‘about’ islands, or an island. These things happen.Last week’s guest, Gaia Holmes’ poems were set in the Orkneys, and a couple of days before that, three of my own about Skye. It wasn’t love at first sight with Skye, where I went for the first time about 30 years ago. In fact, I thought I didn’t like it. It took too long to get there. Everything seemed to be brown unwalkable moorland and rain, and any shop was miles and miles away. But something must have stuck. Maybe it was the one clear October day when we drove along the stretch of road from Ord to Achnacloich and there was the amazing panorama of the whole of the Cuillin with snow on the tops, and a sea as blue as flowers.

Whatever. Somehow I was lost. We kept going back, and I learned, by walking, more and more of the south of the island. How to learn to use deer and sheep tracks. How to see the weather before it reached you, how to walk in boggy land. How to deeply distrust all Scots walkers’ guide book for their terse understatements, the way they say things like: the footpath peters out after a mile or so but the way ahead is never in doubt. Leaving you lost in a corrie 2000 feet up.

I started to collect the literature and poetry of small islands, the histories of dispossession and uprooting; writers like Kathleen Jamie, Robert Macfarlane and Adam Nicholson. Also, painters of wild shorelines like Len Tabner and the wonderful Norman Ackroyd.

I started to learn the stories of abandoned settlements, and of individual ruined crofts, say, at Inverdalavil, or Boreraig, or Suishnish, or Leitr Fura. How some were cleared by forced eviction, and some by sheer poverty and emigrations, or by the need to live where the children could go to school. I started to read about it, and eventually learned that I was romanticising it all – no less than the National Trust/ Clan Donald guides at Dunvegan Castle with their kilts and tartan and Flora Macdonald – and knew less than nothing. I went looking for ghosts among the stones, when what I needed to do was to ask questions and listen to the people who actually lived there. I learned that when I was telling my friend Effie how we’d walked to Dalavil, how we’d sheltered from a storm in a ruin of a croft near the shore.

” Ah yes. Well, Lachlan that was my uncle.

He was born in there. Yon house. Says Effie.

Oh, but it was years ago.”

And that put me in my place. In more ways than one. Islands, abandonment, the misappropriations of history. The business of putting the record straight.

That’s the stuff of today’s cobweb strand. And one more thing. Our last two guest poets (as opposed to gems revisited) have been Irish poets. From the North. Which brings us to today and a poet from Northern Ireland who writes about islands that once were populated and now are not. So, without further ado, it’s my delight and pleasure to introduce Stephanie Conn. Actually, she’ll introduce herself:

“Well, here I am approaching forty and embracing that old favourite Life begins…!

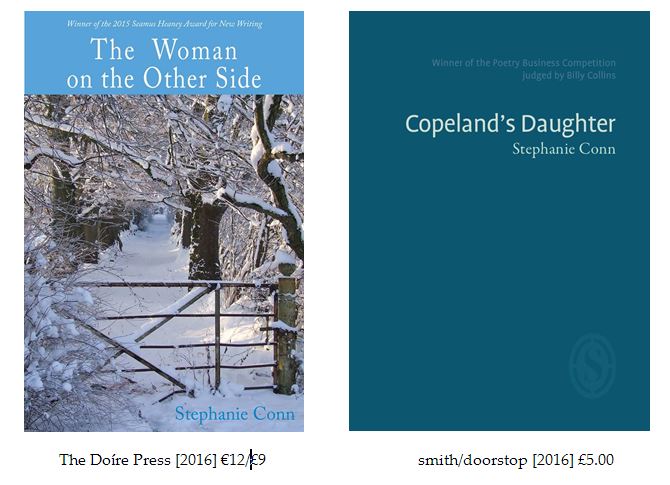

Thirty-nine has been good to me. I launched my debut collection, ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ with Doire Press in March 2016 and in an unexpected turn of events, having been selected by Billy Collins (what a thrill!) as one of the winners of the Poetry Business Pamphlet Competition, three months later I launched my pamphlet, ‘Copeland’s Daughter’.

Now that I’ve told you my age, I can admit to being born in 1976, in the market town of Newtownards in Northern Ireland. After school I attended Stranmillis Teacher Training College, Belfast and studied English Literature as my main subject. Following graduation I started my teaching career in 1999.

My twenties were spent teaching, developing the literacy programme Passport to Poetry,facilitating creative writing workshops in schools and being mum to two daughters. In my early thirties I began writing more regularly. I tried carving out writing time, joined a writers’ group and began submitting poems to journals and magazines. I received encouragement and decided to apply to the Masters Programme at the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University, Belfast. Between 2010 and 2013, I completed a part-time MA in Creative Writing under the tuition of Ciaran Carson, Medbh McGuckian, Leontia Flynn and Sinead Morrissey.

During this period, my poems were being published more regularly and I submitted work to poetry competitions. In 2012, I was shortlisted for the Patrick Kavanagh Award and highly commended in the Doire Press Poetry Chapbook and Mslexia Poetry Pamphlet competitions. It was extremely encouraging to learn that the work was connecting with others. The following year I was selected for Poetry Ireland’s Introductions Series.

I was hooked but by the time I completed my MA, I was back teaching four days a week and due to return to a full-time position in the next academic year. My writing was going to have to take a back seat for a while – or so I thought. I became ill, was unable to teach and spent the following year having assessments, tests and scans in a bid to determine what was causing my symptoms. I was eventually diagnosed with Fibromyalgia. Medication helped but the life I had known was gone and I felt stripped of my identity. There were so many things I could no longer do but I could still write and now I had the chance to commit fully to it.

I started working on new poems and began to arrange a full manuscript. I then submitted ‘The Woman on the Other Side’ to Doire Press and was thrilled when they accepted the collection. In 2015, as well as being highly commended in the Gregory O’Donoghue Poetry Competition and coming third in the Dromineer Poetry Competition, I won the Yeovil Poetry Prize, the Funeral Services NI Poetry Prize and the inaugural Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing.

By the time Doire Press had decided to publish ‘The Woman on the Other Side’, I was already busy with new work. I received an Artists Career Enhancement Award from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland to research and begin writing my second collection, inspired by my ancestors who lived on a small island in the Irish Sea. I submitted a selection of these new poems to the Poetry Business competition.

The last few months have been spent giving readings and facilitating workshops, and I’m looking forward to taking part in a few local literary festivals, before heading to the other side of the world for the Tasmania Poetry Festival in the autumn.

There’s a c.v. to make you sit up! I met Stephanie for the first time in Grasmere a month or so ago, at the Worsworth Trust… the prize-giving ceremony for the Poetry Business Pamphlet competition winners. She read from her pamphlet Copeland’s daughter, and blew me away. The Copelands are a small group of islands of the coast of Northern Ireland, and the poems tell tell the story of her ancestors who lived and farmed and fished there, until they were forced to leave, like so many who have struggled on poor land and in hard weathers, like the ones forced from Mingulay, from the Blasketts, the Shiants, St Kilda. So many. But you can see how these poems ticked so many boxes for me. And she reads with a passion, and a clarity. I was sold from the very first poem: The first lighthouse…Cross Island 1714. A lighthouse in ‘these twenty acres’ that ‘never did attract the sun’

‘three storeys of island-quarried stone, picked

and carried on the convicts’ backs.

They built the wall two metres thick’

Billy Collins wrote of this poem: “The First Lighthouse” should be read in every classroom. I know what he means. It has the same kind of heft that I love in Christy Ducker’s work…coincidentally, in Skipper, the core of which is a sequence about poems about small islands , The Farnes, and the story of their lighthouse, and of Grace Darling.

Of Stephanie’s writing Collins says :

Precise description rendered in physical language lifts these poems off the page and into the sensory ken of the reader.

Well. Yes! And there we are, language that places the reader in this place of punitive hard graft, unrelenting weathers and unyielding material.

And a place, as you see from the photograph, capable of great beauty, which Stephanie celebrates in this lovely collection. She sent me two poems that will give you a taste for it. Promise.

Winter

We are cut off from the mainland again;

a pile of unopened letters sits in Donaghadee;

there is flour and salt and treacle in the grocer’s,

bags of coal and paraffin to fill the empty tins,

but the boat keeps close to the harbour wall.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

Still, the bread is baked and the butter churned,

the blocken cured and the rabbits trapped,

mussels are plucked from the island pools

and pickled in jars on larder shelves.

The firewood and driftwood is stacked.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

Inside the lamps are lit and curtains pulled,

while out at sea, the wind and waves confront

each other in torrents of eddies and pools

and the gulls circling above the spume

could be vultures in the thick sea-mist.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

But we know what the darkness brings;

it drags us from sleep into nightmare, lost in fog

we’ll be struck by ship after floundering ship;

forced into the driving rain, where muffled voices call

from their wreck. We’ll run to the shore to save all we can.

Tide in, tide out and the beam of light,

and a distant moon – waxing and waning.

In a place such as this, we are used to the ghosts,

but not to their dying; never to the bodies of young men

washed up on the shore, with their puffed up faces

and gaping sockets where the eyes should be; or the tiny crab

emerging from a silenced mouth to scurry, ever sideways.

What I really like about this is the side-by-side-ness of the routine management of household comforts, the self-sufficiencies when the boat can’t come from the mainland, the security of a storm bound house….and the way the ghosts of the drowned will find their way in, one way or another. For me, the poem turns on one plain observation that make me re-evaluate everything I’ve just read.

In a place such as this, we are used to the ghosts,

but not to their dying

It has such resonance. I understand those kinds of ghost, how we are rooted in our pasts and histories. That’s the first poem of the pamphlet, and this one is the last.

August 25th

A good day for starting out, or so it seemed

to the Royal Society who sent Cook sailing

off into the Atlantic, round Cape Horn, journeying

westwards to Tahiti to record the Transit of Venus.

And Webb agreed; diving off Admiralty Pier,

smeared in porpoise oil, to swim the Channel;

keeping his stroke steady, despite the jellyfish stings,

the churning currents off Cap Gris Nez, to Calais.

A bride’s dress rests below the collar bone,

covers pale skin, tightens at the waist.

The gladioli stems are wrapped in green satin

to draw out the glint of peridot at her neck.

A gold band placed on her steady finger

is loose enough to pass over the knuckle.

She will search out the star-maiden in the sky,

follow a small black disc across the moon’s face.

Gallileo offers up his newly ground lenses.

The lawmakers ascend the city belltowers,

lift the telescope to their eyes to see the sails

of distant ships, distinct and impossibly close.

Voyager 2 draws as close as it has ever been

to Saturn’s rings of ice-particles and dust,

ammonia crystals create a pale yellow glow

in the dark space where sixty-two moons orbit.

Her great-grandchild wears crushed silk,

exposing sun-blushed skin, thin wrists.

The gaping heads of lilac poppies

lie against her trussed up breasts.

There is an exchange of white-gold rings.

Her body is cloaked in sweat and trembling.

The black sky shines with a thousand

stars that burned out years ago.

As you read through the pamphlet (and you really must), you live through the day-to-day histories of Stephanie’s people, the generations who worked the Copelands, apparently contained in a small tight world. But all the sea and sky are beyond, and this poem explodes outwards into a barely charted universe that offers no answers or direction. The bride is a voyager. I think it’s stunning .

So thank you, Stephanie Conn, for being our guest today. Go well and be well. Tasmania! Half a world away. Read them this last poem. I think that would be fitting.

Next week brings no islands, and indeed, no Irish poets. But we’ll be revisiting one of my very first guests, and I’m really looking forward to it. In the meantime, get your chequebooks out, or head to the Paypal icon. You really have to buy these two books.

This really touched a spot…my childhood summers spent at Ballyferris…along the road from Donaghadee and the Copelands…watching the lights from the lighthouses and the old lightship as I lay in the caravan gazing out to sea…then also off to Stranmillis to train. Now just down the roadfrom you John n Warrington married to a potter…and following your wonderful blogs every week. Thankyou.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, you’ve made my day, Geraldine. I love the idea that my living near the M62 near Wakefield means we’re just down the road from each other. Plus I’ve been having the Blogger’s Doubts. Writing away, convinced there’s no one reading. Thank youxxxx

LikeLike

How wonderful to hear, Geraldine. x

LikeLike

Beautiful! I can see why Stephanie Conn was a Poetry business pamphlet winner-such lovely writing. Thanks for sharing her work here John…p.s. please don’t doubt your blog- i don’t always read it but it is always a great surprise and pleasure to find writers i’m not familiar with ( or work i don’t know from poets i do) when i do drop in….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, Charlotte. x

LikeLike

Charlotte, you are a joy and treasure. All doubts dispelled xx

LikeLike