Promises to keep and apologies to make; it’s been too long since the last post. I may be part-Troll. I may be like Detritus in Terry Pratchett’s stories…our brains don’t work in hot weather.

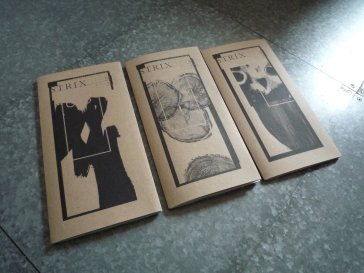

Which is how I started the last post..feeling guilty about not posting every week, but basically too busy. Mainly with home improvements and hospital appointments, but also with very enjoyable poetry events. It was lovely to go to Leeds a couple of weeks ago to read at the launch of Strix‘s fourth issue. What an achievement that’s been for them. Should you not know about Strix, it’s a new magazine of poetry and short fiction. In its first year of publication, Strix has been admired by Carol Rumens in The Guardian (‘—handsome, streamlined and sharp-eyed’) and was shortlisted for Best Magazine in the prestigious Saboteur Awards. Strix is edited and published from Leeds, England. The editors are SJ Bradley, Ian Harker and Andrew Lambeth. They have done a quite remarkable job, and are now attracting hundreds of submissions. Watch out for Strix. It is, without doubt, a lovely thing.

Even nicer was to read at the Leeds Library, founded in 1768 as a proprietary subscription library and now the oldest surviving example of this sort of library in the British Isles (it boasts Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) as one of its original subscribers) and celebrating its 250th anniversary this year. It’s an astonishing place, right in the heart of the city centre, and probably not known to the bulk of the folk of Leeds. If you’re ever in Leeds, give yourself a treat and go in for a look round. It’s on Commercial Street, tucked in behind and above the Co-op Bank. The first time I went was earlier this year to hear my hero Tony Harrison, so there was a real frisson to be able to read where he’d read.

At the end of July I was reading at the third launch event of my new pamphlet Advice to a traveller. And what a lovely night it was, with guest poets Laura Potts (it’s high time a smart publisher snapped her up) and Ian Parks, and a travelling enthusiastic audience from Mexborough and Doncaster. Made all the complications of organising venues worthwhile. And thanks to the staff of Wakefield’s Red Shed which is a really nice place to read and listen in. Thank you, everyone.

But what about that clock, and that winged chariot? I’m cautious about how I explain this. I don’t want to give the wrong impression. Maybe I should say, before I crack on, that I am fit and well and happy…no qualifications. Hold on to that thought. I’ve noticed for the last couple of years I’ve been writing what might seem bleak-sounding poems, a bit dark, a bit valedictory but not particularly backward looking or nostalgic. More concerned with the fact of death being a lot closer than it was not so long ago. I believe your poems are like dreams..you have less control over what they say to you than you’d like. Or at least, the good ones, the important ones, do. Behind them all is the acknowledgement that at 75, your days are numbered, and you begin to accept that you’re not immortal. It’s not distressing (well, not to me, anyway) but it means that sometimes you’re looking at life through a diminishing lens you need to understand and get used to. And it also means, for me, that everything becomes more interesting, and I don’t want to waste a minute. I’m in a hurry to do stuff. I can’t hang around fine tuning poems and pamphlets. I want to write and write and get it out there.

At my back I always hear time’s winged chariot hurrying near. Curiously, I’m untroubled by the concept of deserts of vast eternity, and I don’t think Marvell was, either. To his coy mistress is a young man’s vision in a young man’s poem. Because, I believe, he hears nothing of the sort. He’s in a hurry, but not because he thinks he’s going to die any minute soon. The one who speaks to me these days is Norman McCaig. A couple of years ago I set myself the job of reading his collected works, a few poems every day for a year.

By the time I reached his poems written in the 1980’s I started to notice images of approaching death. The horse that comes along the shore, the black sail in the bay, the scythe in the field, the immanence of journeys ending. I wondered why, because I didn’t know much about his biography. I noticed poems that mourned the death of old friends. The penny dropped a bit later. In the mid-1980’s he was the age I am now, an age when some of your oldest friends, all about your own age, have died. The thing is, he had nearly 15 years left to live, but he wasn’t to know that. And most of his poems go on being vibrant with life and the love of life. He went on walking in the Sutherland hills, fishing the remote Green Corrie. He became frail in the 1990s, but he wasn’t frail when he started noting the finite nature of things. I see what he meant. Time has changed its meaning. It is too precious to not do things in. It makes life more urgent, more vivid. I can’t get enough of it.

It would be slickly ironic to say that time is wasted on the young. It isn’t. I’m a firm believer in the value of wasting time, of faffing about, of being bored when you’re young. I suspect that boredom is the mother of creativity, eventually. Though I’m massively impressed by the energy and drive and hunger of young and youngish poets I know. Poets like Kim Moore, Laura Potts, the perennially youthful Clare Shaw. They make me more alive. I don’t know how they manage it, but I’m grateful. And equally grateful for the company of younger* poets I meet in writing workshops, who have all the time in the world, but (unlike me at their age) believe in cracking on, and writing as if they don’t. Which brings me to today’s guest.

*I realise, when I check and proofread this that ‘younger’ is entirely and meaninglessly relative. I suppose, by now, I mean anyone under 50. Eventually, it’ll be anyone with most of their own teeth who’s nippy with a Zimmer frame

When I started writing the great fogginzo’s cobweb I only knew that I wanted to provide a platform for poets who you might not have come across, poets who hadn’t yet been published, but poets who wrote things than I wanted to share. It was a way of saying thank you to the ones who had shared my poems before I’d had any published. Which, in turn, is why I wanted to write more and write better, to justify their faith.

This will be the third post to introduce the work of poets I meet at The Albert Poets Monday night workshop group in Huddersfield. You’ve met David Spencer and Regina Weinert. Now meet Jack Faricy. In fact, let him introduce himself:

“I came late to poetry both as a serious reader and as a writer. I’m an English teacher now but even that was an afterthought. My first degree was in Economics and French. It was only after a few months working in an insurance company that I realised what a terrible mistake that had been.

I taught English as a foreign language for close to a decade (Thailand, Japan) and completed an MA in Linguistics by distance learning. This enabled me to return to the UK and study for a PGCE.

I’d started reading more contemporary poetry but creative writing had always felt like something for other people. I’d made the mistake of admiring elitist authors who could be savagely dismissive of aspiring writers with ‘provincial’ backgrounds.

But the itch outgrew Martin Amis. I wrote my first ‘real’ poem after experiencing grief. It is a landscape poem that is not obviously about loss. I found I couldn’t stop, especially after enjoying the support and encouragement of friends at The Albert’s Monday workshops.

Now, sitting down to write feels like housekeeping. If I didn’t do it, chaos would rule. Giving shape to an idea or a feeling allows me to file it away and start afresh. And once everywhere’s clear, I can start messing things up again.

I have had poems long- and short-listed in a number of competitions. ‘Tom’ was highly commended in the 2016 Red Shed Poetry Competition and ‘Spoor’ was the People’s Choice for Best Poem in the 2017 Canterbury Poet of the Year Competition.”

I really like that:

Now, sitting down to write feels like housekeeping. If I didn’t do it, chaos would rule.

I’d never thought of it like that. Housekeeping. But yes, that growing awareness that things are not where they should be, neglected, a bit dusty and grubby, ideas neglected, jobs unfinished, stuff left lying around. Writing as ‘putting things in order’. Yes. And now, the poems.

Spoor

His silt-soled footprint fits like skin;

its mud-mould gives

a little, goads the nuzzling toes

and flexing arch.

I try to feel my way in, discern

the pulse of his veins,

hunt-quickened, alive

to some new cunning in his prey. My eyes

strain to be his, not blurred

and blinking in the wind, but whetted

keen, flashing and darting

as he harries an aurochs

to death, heedless of shapes

left in the sand to harden, become relics

of the chase, like this

fragment of his scattered form.

Nothing. We share nothing

but this tide-washed stratum.

My foot’s a blindworm

thwarted in its burrowing, nostalgic

for its cast-off skin.

I turn back to the dunes. A boy

digs; his mother, deck-chaired,

wind-shielded, hugs herself for warmth,

waves. I retrace the steps between us.

This poem reminds me that Jack’s poems have two qualities that particularly grab my attention. One is the quality of curiosity coupled with a wide frame of reference; you can find yourself anywhere in the world or in history. The other is the way he will seize on the moment that draws you in, and then speculate about its back-story, which is often (but not invariably) presented quite filmically. So we start with the fossil record of the momentary impression of a long-dead hunter, his single footprint in estuary mud, then strain to see through his eyes, and fail. My foot’s a blindworm. I think this image nails it. We’ve reached a dead end, and then the focus shifts, as it does in film, back to the living and loved. We have been away too long. I love the ambivalent tone of that last line:

I retrace the steps between us.

knowing that the waving woman cannot know how far away in time he has been.

Three more poems, then, that share this business of digging into the meaning/significance of ‘the moment that draws you in’. The next ones, I suppose, more purely imagist. But I like the irony of it very much

Tinkling Cymbal

Pylons vanish up, cables slung

over crawling traffic and a field

where blackthorns claw the mist.

Motionless on a hoarding’s rim

a peregrine falcon digests its prey

above a quote from Corinthians.

Drivers see mirrors and screens,

their vehicles passing like sand

through the neck of an hourglass.

( I assumed, wrongly, at one workshop, that everyone would know the Corinthians reference in the title and link it with the image of the billboard parked on the embankment. Who hires those advertising trailers? Who rents the field space. Who wants to admonish me and pay to do it? Anyway, here’s the reference, in Tyndale’s version:

Though I spake with the tonges of men and angels and yet had no love I were eve as soundinge brasse: or as a tynklynge Cymball.

The next poem starts with an image, and then, like Spoor, takes in a swoop of time back through two millennia, eliding the the hubcap that spun away from the collision with a Roman legionary’s shield, the moorland road and golf course coinciding with a Roman road, the inflated plastic heart of an impromptu roadside shrine and the small flag of a golf course pin fluttering at the site of a brutal execution.

A tethered heart twitches

in shivering wind.

Traffic cones sprout bouquets that buckle

under sleetfall. The toppled wall bleeds meltwater

into runnels that thread the way

from Rocking Stone to Cambodunum,

Slack’s ROMAN FORT (site of).

This unrecovered hubcap’s where

a Cantabrian sloughed his shield

to piss insults in the snow.

A flagged pin piercing Petty Royd,

the longest par three in Yorkshire,

points to his deathplace. Cudgeled

for breaking rank, he lost his hold.

Gusts tug the jittering heart.

I was judging The Red Shed poetry competition a couple of years ago when this last poem turned up in a batch sent by the organisers. It jumped out, snagged my attention, drew me in. I liked the disingenuousness of it; I liked the way it it somehow manages to bring irony and empathy and caustic humour together. I like the deadpan tone. And I genuinely had not known about the anagram.

Tom

If you only could have known,

looking out over Margate Sands

in the wake of your breakdown

and summoning The Waste Land’s

middle section, that the shelter

where you surveyed the wreckage

of washed-up humanity, and felt the

burning allure of unholy Carthage

still stands and, as if in allegiance

to your enduring fame,

now faces a public convenience

bearing an anagram of your name,

then there’d at least have been something

you could have connected with something

So, thank you Jack Faricy…for the poems, for the idea of writing as housekeeping, and for connecting all kinds of things with all kinds of things, and playing games with time, reminding me that

Hello John, I enjoy your posts- always look forward to reading them. I have you to thank for my love of Tony Harrison- you told me a story about meeting him and gave me one of his books. I felt such a connection to his poems and still do. He lives in Newcastle I think.

The first time I came across Norman MacCaig was at school in Gateshead, in the late 70s early 80s, in an anthology called ‘Worlds: Seven Modern Poets’. It also had Charles Causley, Seamus Heaney, Ted Hughes, Thom Gunn, Adrian Mitchell and Edwin Morgan and was edited by Geoffrey Summerfield. I loved it, I used to sit at the back of the class and just read the poems and not take part in the English lesson. Norman MacCaig really interested me and I have always felt was, for many years, not recognised enough in terms of introducing children to poetry. He never appeared in my education at school, university or in exam syllabuses whilst I was teaching – just not ‘fashionable’. I love his humour and the simplicity of his language and imagery. Hope you are ok.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like Charles Causley, McCaig was underrated by the poetry establishment for years. Not ‘modernist’ or ‘cutting edge’. Or something equally pointless. But he was loved by anthologists like Summerfield who introduced him and lots of others to generations of schoolchildren and older students. “Worlds’ was an important book in so many ways, as Anthony Wilson (and me) have pointed out in our blogs. “An ordinary day’ was the McCaig poem in lots of school anthologies, which was how I met him. Thanks for reading and following the cobweb. Much appreciated xxxxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘So Many Summers’ is one of my favourites from Norman MacCaig. So simple and true.

LikeLike

I’ve been looking forward to your blog on Jack Faricy, so thank you and Jack for those poems. I like how they are so solid, and strange, unflinching, how strong the images are in containing fragility and connection. Fascinating too, the idea of writing as housekeeping.

And again I love the photos, especially the sea-scapes.

Regina

LikeLike

Aww…thank you for that, Regina xxx

LikeLike

Thanks Regina. That’s lovely to read. I forgot to mention, John, that I also love the images. I spend a lot of time googling for images to match poems I teach in class, so I know how long it takes!

Jack x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good fun, googling xxx

LikeLike